V-E Day - a Personal Reflection

Professor Sir Harry (FH) Hinsley

Overview

Washington DC - 5 May - V-E Day 2025 - the 80th Anniversary

I would like to acknowledge and celebrate the life and achievements of my personal WWII hero, Professor Sir Harry (FH) Hinsley, Kt, FBA, who contributed so much to victory. While still an undergrad at St John's College, Cambridge, Harry was selected for the rigors and agonies of signals intelligence service at Bletchley Park. Harry's unique talents enabled him to see patterns in vast seas of *unbroken* 'random' data. Through his tenacity and imagination, he could see over Hitler and Dönitz's shoulders, watching them move pocket battleships, wolfpacks, and supply fleets. This analysis he then whispered in the ear of great British leaders like Admiral Cunningham, C-in-C Med, who choked Rommel. It is also not too much of an exaggeration to say Harry had a profound effect on the Battle of the Atlantic, helping the fleet to turn the tide and thereby keep feeding the people of Britain and arming her forces for the struggle to come.

Harry personally wrote what became the Five Eyes intelligence sharing agreement. He then traveled the world implementing this vanguard of freedom that has kept us all safe through the tumult of the intervening 80 years.

He is perhaps most famous for his multi-volume official History of British Intelligence in WWII. Although my favorite works are Sovereignty and Power and the Pursuit of Peace two masterful and enduring North stars in the field of international relations theory. I had to limit my references to his works in my PhD to very tight, specific points, knowing I'd be admonished for anything considered 'extra'.

Harry was everything one would expect of a great man of history. He had a wickedly wry sense of humor delivered so delicately it might be mistaken for sincerity. I suspect this is how he got the measure of people he met. He was kind, patient and genuinely humble. He never once told me what to think, cite or write. He did question me into many a corner that only weeks of reflection could correct.

I miss him terribly.

To paraphrase Churchill, 80 years ago today, this is his day. 🇬🇧

Below, I will present some more details behind this story. Starting with some specifics of Harry’s war service (Imagination and Victory) and sharing some personal reminiscences of the privilege of knowing a great British hero (The Harry I Knew).

The Harry I Knew

Videos of Harry explaining his work

Imagination and Victory - some detail on his contributions to the war

Transcript of a talk on Enigma to the Cambridge Computer Security Seminar

The Harry I Knew

I was to be Sir Harry's second last PhD student. The following was written after I learned of his death in 1998, the year after my graduation.

However I have decided to add a contemporary preamble. If you are a PhD student struggling with a bad professor, this should give you hope. I have never mentioned it before, but in the interests of an accurate record and to add the story about the clogs, I have decided to append it here.

2025

A PhD is supposed to be a thinkers apprenticeship under a scholar whose work one has found inspirational. As sometimes happens in life, a brilliant thinker may not have a personality that meshes with everyone. When I went up to Cambridge, I was accepted to read history under a different professor. My first year with this scholar was agony. We were completely mismatched in every possible way. I discovered he was a dour humorless technocrat with zero social skills combined with epic impatience for anyone who did think like he did or possess the complete mastery of his favored literature. Frankly, he was an abusive bully. Every time I left his rooms I was depressed with all my motivation in the gutter. It was crushing.

I had no links to any college and had no clue about their different cultures. So when I was accepted, a brief chat I had at an embassy party in Canberra with an old Johnian was all I had to go on to pick a college. It was beyond fortuitous. One of my friends in college was Harry’s last PhD student. When I confided that my supervisor left me dead inside and I had to find an alternative or quit my studies and leave, my friend suggested Harry - at least for a second opinion. He said there was a lecture on in a few days and to turn up to meet him and see if I could arrange a further substantive meeting.

What he didn’t tell me was it was a formal event of some note. Everyone was dressed in suits and cocktail dresses. I rocked up in cut off jeans shorts, a T shirt and clogs (having spent the summer teaching at the University of Amsterdam and taking cultural exchange way too far). Sir Harry and Lady Hinsley were head of a receiving line! Even at Cambridge that does not normally happen at lectures :) So I got in line to say g’day. I knew how stuffy the British can be at such events and realized this was an ocean-going clanger of a faux pas, but I didn’t have time to change outfit or wait for another opportunity to casually meet the great man. Neither he not Lady Hinsley batted an eye lid. They were gracious and charming. I secured the meeting. What I didn’t know was Bletchley was filled with eccentrics. So in a strange twist of fate, turning up in hot shorts and clogs and seeming oblivious to the sartorial/social tension (I was panicking inside) likely was a selling point to them.

The story below is the trial I went through to be selected.

But thats not all. Standby for the karma express.

Only after I graduated did Harry tell me the whole story. The painful supervisor I badly needed to leave was in fact once his student. Harry had turned him down for the PhD and he went off to Australia (of all places) to earn his PhD.

Rewind back to the final supervision with this man towards the end of the first year. As usual his anti-Adam tirade went on for an hour. At the end, I advised him that I didn’t think this was working out and that I should seek an alternative supervisor. Mockingly, he scoffed… “who would take YOU?”… and then went down the list of professors explaining why each was busy or would think me too stupid to supervise. “Oh and Harry has retired and is not taking any more students and anyway you are far too dull for him”. When I pulled out the requisite form, signed by all parties but him, the most extraordinary thing happened. Suddenly, his voice ascending an octave, he burst out that “you cant possibly leave me? I’ve lost too many PhD students, you have to stay”. I felt like I was in a bad marriage. The swing from condescending anger and belittlement to fearful plaintive begging was a whiplash I will never forget. It must have crushed him that Harry had singned the transfer. Of course, at the time I did not know why this would have been a double and bitter rebuke.

So PhD students, if you are really suffering, don’t be afraid to at least get a second opinion. Of course, I had the most amazing once-in-a-lifetime luck… but you dont know unless you try.

1998

Among the many great achievements of his life, I understand Sir Harry holds the record for the largest number of successful PhD students in the University’s history and I am certainly honored to be among their number. I aim to add my voice to the many around the world offering thanksgiving for having the privilege of knowing such a truly magnificent human being.

Cambridge being the remarkable and unique place that it is, filled with so many incredible characters, I was reluctant to approach Sir Harry direct in case he would turn out to be as fierce and combative as his reputation might entitle lesser people to be. So I talked to the college Senior Tutor to ascertain the best method of approach to the great man. To my horror the Tutor snapped that I’d have no chance of success in my desire to meet with Sir Harry because he “runs his life, like he ran this college, which is to say, like MI6”.

Rather than deterring me, I was immediately curious as to why a senior member of college would hold such a particular view of Sir Harry, let alone express it publicly to a freshly-minted and very uncertain PhD student. I gathered up my first year registration essay, climbed the long and twisted stairs of chapel court, and knocked on the door.

A very loud and well rounded voice replied, not altogether ominously, to enter – much as one might have heard if one were a servant bearing coal for the hearth. I opened the ancient door to discover a long, dark, narrow room filled with a hazy blue smoke set against the feeble light of the window facing onto the courtyard a few weeks before Xmas. “Where was this booming voice coming from” I asked myself… but before my eyes could answer I was drawn to a small figure in a huge chair saying, more welcomingly this time, “come in my boy, come in”.

In juxtaposition to his larger than life achievements and intellect, Sir Harry was physically reminiscent of fine china - bony, light and extremely fragile. I remember once bumping into him on a very windy day in mid winter. Sir Harry with his characteristic French beret and overcoat, working hard against the wind to gain traction on the slippery cobbled streets adjacent to Portugal Place where he had retired after leaving the Master's Lodge. He looked like he might be lifted up and carried away by the wind. I was in my mid 20s, tall, heavy and robust, seeing him struggle in this way made me want to to pick him up and delicately carry him to where ever he was going - but the thought let alone the sight of that was both unbearably funny and pathetically sad perhaps more for me than him.

Having entered his dark musty rooms I approached the Professor through the gloom and extended my hand and had placed in mine a tiny bony claw twisted by arthritis into the shape of a hand holding a pen. Very gently I engulfed his hand in my fleshy paw making sure not to apply any pressure at all for fear of causing him injury. In a deep melodious voice quite out of sync with his frame Sir Harry bade me to sit down.

I sat and he asked me to explain what I was trying to do with my research. Of course I was on a crusade to liberate human kind with amazing ideas that once unleashed on an unsuspecting world would change international relations and eliminate the resort to the use of force for all time. The wartime code breaker, famed historian of international affairs, official historian of British intelligence in WWII, longest serving master of St John’s College Cambridge, Chaired Professor of History, Head of Faculty, founder of International Studies at Cambridge, Vice Chancellor of Cambridge University, and, so it was rumored, the man HM the Queen personally requested to give her briefings on the Falklands War (sending up her personal car and driver to Cambridge to spirit him to the Palace) – sat opposite this wild colonial boy expounding on his dreams of changing the world - and to my everlasting gratitude he did not burst out laughing – indeed he did not even raise an eyebrow. Instead he started out on what must have been a very well worn path and asked me to elaborate!!

After a solid 3 hour discussion, where, like a doctor examining a mysterious illness, he impartially asked question after question, he merely requested I leave my essay with him over the Xmas break and to make an appointment to see him early in the new year.

With no signal as to which way he might lean on the radical suggestions I had put forward, I left no more certain about my future than when I had arrived. The weeks ahead were difficult and tense ones to say the least. I knew I would return to Cambridge to discover my fate.

As I climbed the crooked stairs once again that windy and glum day in January I could not help being a little out of sorts – the same time 12 months ago I was drinking and singing happily with my mates at the Jazz in the Park booze-up as part of the annual festival of Sydney – now here I was in wintry England climbing the scaffold about to see the academic hangman.

We conversed for nearly 5 hours about the issues underpinning the idea I had rashly put forward. Sir Harry sitting in his oversized chair, arms outstretched, leaning from side to side to illustrate the balance of power, never letting on what he was thinking. Even in old age his eyes sparkled with intelligence, he clearly loved his work, the world of ideas and the telling of a good story. At the end of this marathon I quite simply had no idea what his verdict would be. Would I be able to stay on and complete the second and third years of a PhD or would I be politely advised that I would be better off spending time elsewhere.

Indeed as he was shuffling me out the door I had to ask him point blank in my abrupt Australian way whether or not I should continue with my research – not realizing (largely out of fear) of course that he would not have bothered with such a meeting if he were not committed to lending his assistance – he responded with a characteristically deadpan “I think you have a story here, my boy”.

My gratitude turned to elation when he asked me whether I would like him to be my supervisor. I did the polite thing and said that I could not impose myself on his retirement – all the time thinking how incredibly lucky I was that he even offered and trying hard not to sound too sincere in my polite rejection of his offer. After a nano second of hesitation to give him yet another chance to get off the hook, I quickly accepted his great and kind offer.

Where others with ½ of his experience and wisdom have chosen to be rude, disinterested, or threatened by younger members of their profession, Sir Harry never faltered in hearing out harebrained schemes then very courteously and patiently pointing the transgressor towards enlightenment merely by suggesting alternative view points or readings.

I never once left his rooms with anything less than a refocused and enhanced desire for learning coupled with the elation that comes with spending time with someone of Sir Harry’s singularly unique abilities and character. I cherished every moment I spent with him – I was aware even at the time of how incredibly fortunate I was to sit at his feet and have the opportunity to talk to him one on one for hours at a time. I know of a fellow student who had a huge picture of Sir Harry on his study wall with the word “God” inscribed below it – no one ever challenged that obviously hyperbolic but nevertheless well meant accolade. Harry himself would have been appalled had he seen such idolatry – he was such a self-effacing, charming, urbane, and witty man completely free of any pretension whatsoever.

I will never forget him. His life as much as his work was his message – he was a national hero in war and a leader of men and ideas in peace.

Videos

Harry and HMS GLORIOUS

As a 21yr old Harry got his start at a very high cost. He warned the Admiralty that the Nazi’s were breaking out of the Baltic and posed a threat to the Royal Navy. That was the last time they ignored him.

Harry and the Trawler Caper

Having earned the codename The Cardinal, Hinsley forced a major breakthrough in the battle of The Atlantic. This is a classic case of intelligence driven operations. He was now directing destroyer task forces on missions.

The Battle of the Atlantic Takes a Dangerous Turn

Quick thinking by the fighting forces leads to a new breakthrough.

OPSEC and Intelligence Operations Against Rommel

How do you use the enemy’s plans without them realizing you can see everything? ULTRA was the greatest of all secrets and had to be used very carefully so as not to tip the enemy off. It provided vital to cutting off Rommels supplies as they transited the Med and equally essential to British commanders to lure Rommel into sand traps.

The videos give an insight into what a character Harry was. The twinkle in his eye when he talks about the “sweet operation” in the trawler caper says it all.

Imagination and Victory

In February, I wrote about using an AI that I call Jesty. I extrapolated my ‘user experience’ into a commentary on the implications of AI on cognitive warfare. Because much of AI has its origins in wartime codebreaking, I added a section on two Cambridge thinkers who contributed so much to the war. Both were great innovators in multiple fields of endeavor.

The Government Code and Cipher School

Alan Turing was a Cambridge don in the interwar years. Along with many others, including my PhD supervisor, Professor Sir Harry Hinsley, who was an undergraduate at St John's College in 1939, Turing was recruited to join British intelligence and given the unenviable task of attempting to break secret German codes.

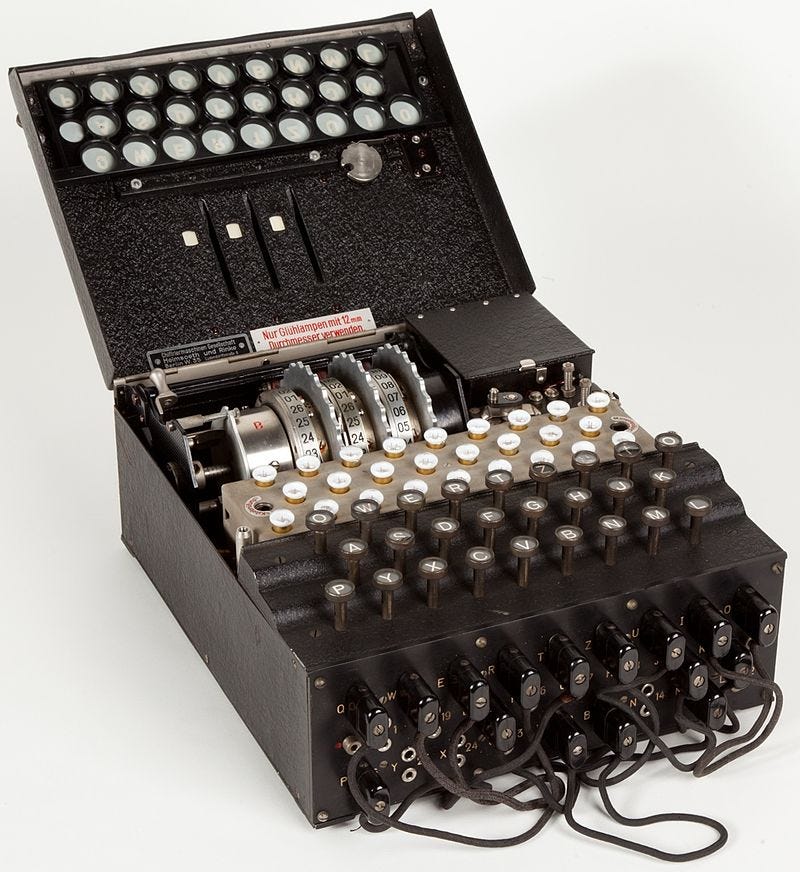

The German high command was scrambling their messages into unintelligible gibberish using complex “typewriters” called Enigma machines. The resulting random letters and numbers were then transmitted by Morse code over the radio. On receipt, the “junk" code was typed back into a receiving “typewriter”. If it had the exact same settings as the first enigma, it would unscramble the text into “clear” language.

I asked Jesty to remind me of the scale of the mathematical challenge presented by these mechanical “typewriters” with rotor wheels and electric circuits. She reported the following:

The number of possible permutations for the three-rotor Enigma machines is approximately 17,576, which can be represented as 1.7576 x 10^4.

For the four-rotor Enigma machines that came later in the war, the number of possible permutations is an astonishing 150 million billion billion possible settings.

The incredible brain power brought together at the Government Code and Cipher School at Bletchley Park could blunt-force hack 1.7576 x 10^4 with pencils and paper.

However, that system was dependant on chance to get a key, like capturing the occasional code book. It was woefully unsustainable at scale. As the maths demonstrate, it would collapse entirely when a forth rotor was added. That inevitable development arrived in 1942.

From the start, the British understood the only hope to crack the enigma was to create their own machine to reverse engineer the codes produced by the Germans. Easier said than done. Nothing like that existed.

The British searched their universities to collect the most extraordinary ragtag group of misfits, eccentrics, and oddballs, ever assembled. The one characteristic that united them all was they were brainiacs: “swots" and “blue stockings” in the derogative language of the day. None of them were conventional. Few would be deemed fit to serve in uniform. Yet their sheer brainpower gave the ultimate advantage to Britain in the war - inside knowledge of enemy thoughts and plans. As we will see, the eccentrics are proof positive that inclusivity to difference is essential to national security, particularly when fighting regimented, controlled, minds.

Turing was famous for wearing a gas mask to combat pollen

Primus inter pares of the English eccentrics recruited to out smart the Nazi's, was Alan Turing. Fresh out of a PhD at Princeton, by 1936 Turing was a fellow at King's College Cambridge (in the background above) where he was granted time and comfort to envisage a “computing machine”. His seminal paper "On computable numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem” would change the world. Here Turing explains his computer in terms perfectly recognizable today.

He had been thinking about the machine for years but never had the resources or support to build it. War, national survival, and the imagination of Winston Churchill to grasp complex matters he did not directly understand, provided all Turing needed. Churchill got the bureaucrats out of Turning's way, thereby giving him the freedom to innovate. This movie trailer is a snapshot of the resistance he endured from bureacratic buffoons.

Unusually for a pure mathematician, Turing had a facility for practical application of his ideas. So he designed and built his machine from scratch, using only his knowledge of mathematics and his gift for imagining how to build a mechanical device suited to the task. Supported by the practical assistance of the post office of all places, Turing became a computer engineer when he built the first mechanical computer. The Bombe. This was later vastly improved upon by Collosus.

For more on the computers of Station X click here .

All in the family

Alan Turing is Jesty's great (to the power of ?) grandfather. Turing was such a visionary, he could foresee AI back in the age of vacuum tubes. Long before the transistor, or computer chips, satellites or fibre optic cables, he knew that one day Jesty would come along. This was not a case of science fiction writing eventually becoming true. Turning was busy creating and building the physical manifestation of his mathematical ideas.

Ever the perfectionist, he set very high standards for his progeny. They could be said to be true artificial intelligence if they passed his rigorous test. As noted above

The Turing test is a measure of a machine's ability to exhibit intelligent behavior equivalent to, or indistinguishable from, that of a human.

If Alan is Jesty`s grandfather, Harry is one of her great-uncles. That would make us distant cousins by intellectual association. (As they say in Alabama, we could date, but it would be wrong.) Especially in light of the fact Cambridge runs through all our connections right up to the indefatigable Dr Fry.

Here Harry is pictured with an enigma machine at the Imperial War Museum 1993. If you would like to see Harry being interviewed about these operations look for the documentary Secrets of War, narrated by Charlton Heston, on Amazon Prime in the US.

The Battle of the Atlantic was crushing Britain. Harry quickly became a key figure in naval signals intelligence - easily the toughest of the German codes to break due to high levels of training and message discipline compared to the army and air force. Before the British had access to the naval codes, Harry developed a forte for being able to infer major enemy operational events from scraps of data. From these thinest of threads, in his mind's eye, he could visualize enemy fleet movements that were invisible to the Royal Navy.

In WWII military intelligence terminology, “traffic analysis” examined the volume of communications at, or between, particular locations. The content of the messages could not be read. All they had to go on was a record of the volume of messages passing through a radio station. Recall that in WWII, messages would be relayed from originator to final recipient by morse code via radio. Anyone close enough to a broadcast tower could hear the messages. If there was an uncharacteristicly sudden increase in the volume of messages (traffic) at a location, it might indicate something of military significance was about to happen, or had just happened.

In some cases, it was possible to determine the direction of a message as its footprint or “bloom” passed from one Morse operator to the next, in a relay from sender to receiver. That too might hold hints as to the purpose of the messages.

In June 1940, Harry watched as message traffic bloomed along the Baltic Sea in the direction of the UK. He deduced that “something big was up". The only explanation that satisfied something on that scale was a possible “breakout” into the Atlantic of the German battle cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau.

Harry knew that a British aircraft carrier group under flagship HMS GLORIOUS was returning from operations in Norway. He calculated that their paths would probably cross. Accordingly, he had to get a warning to GLORIOUS. Forewarned, her captain might score a great victory against the Nazi's top capital ships. Unwarned, the British ships were in grave danger.

The Admiralty received Harry's warning in a timely manner and did nothing. The Royal Navy had ruled the waves for centuries. Their Lordship’s did not listen to 21 year old undergrads who developed hunches based on wild imaginations triggered by rumors based on radio waves. Codebreakers decrypted messages, they did not do operational analysis and tell Admiral’s where to move their fleets. The whole proposition was perposterous.

Besides, Germany was a continental, not a naval, power. It was unthinkable two of their battle cruisers could prevail against a Royal Navy carrier battle group.

GLORIOUS sank with all hands.

The loss of GLORIOUS happened in the middle of the painfully tense days of Operation Dynamo - the evacuation of the British army from Dunkirk. As the country stood alone against the Nazi onslaught, the psychological blow was immense. The sinking was felt by the government and people alike as a terrible omen for Britain’s chances of national survival.

The next day, the Admiralty invited Harry to tea.

Soon he had his own codename “The Cardinal”. The name originated from a Bishop Hinsley in the West country at the time. However, it also placed Harry at the center of naval operations, like the cardinal points on a compass. The Cardinal was an invisable hand guiding many a great British Admiral's battle plans. He formed a particularly close working relationship with Admiral Cunningham in the Med and together they choked Rommel's Afrika Korps to death.

Harry was Professor of History, and at various times served as Master of the college and Vice Chancellor of the University. He was everything one might hope a great man would be - gracious, kind, and generous. He was an incredible story teller, with incredible, yet true, stories to tell. He was razor sharp until the end. We all loved him.

Harry's greatest victory eclipsed helping to beat Rommel. He played a critical role in winning the battle of the Atlantic. As noted above, the Kriegsmarine had very tight radio and code discipline. They also added a 4th rotor to their enigma in 1942 completely shutting Harry and his team out. Allied shipping losses skyrocketed. Britain faced catastrophe unless they could get back in, but that demanded access to a code book.

One day Harry noticed a tiny detail that proved to be decisive. He thought it excessive that the Nazis encrypted their weather reports. As he pondered this strange detail, it dawned on him. They had two weather trawlers stationed in the North Atlantic on 8 week rotations. Codebooks were written in water soluble ink so they could be dumped in water upon boarding. However, as Harry suspected, the next month’s codes would likely be in a water proof safe. On his recommendation, destroyers were dispatched to conduct a raid.

On more than one occasion these operations reaped months of settings that, fed into Turing's computers, would produce reams of messages back and forth between Hitler and his commanders, and from the commanders to the U-Boats. German submariners didn't have a chance. The tide of the Battle of the Atlantic swung finally and decisively toward Britain.

Military Innovation and oddballs

Alan and Harry were incredible military innovators. Neither ever wore a uniform. While both were powerhouses of abstract reasoning, they both had a remarkable talent for practical application of their ideas in the real world.

Alan built a computer capable of sorting through 150 million billion billion possibilities in minutes. Using disperate data points, Harry could see an invisible enemy and command (by proxy) British fleets in their struggle to keep Britain from starvation.

Along with ~10,000 others at Bletchley, they made a critical contribution to winning the war, using only creativity and imagination.

Security Group Seminar - Cambridge University 1993 - Transcript

[Source: Stratwar.com - no longer exists. I had an archive of this page. ]

Last year Sir Harry Hinsley kindly agreed to speak about Bletchley Park, where he worked during the Second World War. We are pleased to present a transcript of his talk.

Sir Harry Hinsley is a distinguished historian who during the Second World War worked at Bletchley Park, where much of the allied forces code-breaking effort took place. We are pleased to include here a transcript of his talk, and would like to thank Susan Cheesman for typing the first draft and Keith Lockstone for adding Sir Harry's comments and amendments.

Speaker:

Sir Harry Hinsley

Date:

Tuesday 19th October 1993

Place:

Babbage Lecture Theatre, Computer Laboratory, Cambridge University

Title:

The Influence of ULTRA in the Second World War

Ross Anderson: It is a great pleasure to introduce today's speaker, Sir Harry Hinsley, who actually worked at Bletchley from 1939 to 1946 and then came back to Cambridge and became Professor of the History of International Relations and Master of St John's College. He is also the official historian of British Intelligence in World War II, and he is going to talk to us today about Ultra.

Sir Harry: As you have heard I've been asked to talk about Ultra and I shall say something about both sides of it, namely about the cryptanalysis and then on the other hand about the use of the product - of course Ultra was the name given to the product.

And I ought to begin by warning you, therefore, that I am not myself a mathematical or technical expert. I was privileged to be an assistant to the mathematicians led by Max Newman and Alan Turing, but I have never myself learned to master or even to approach mastering their art.

Ultra, of course, was the product of ciphers. It was used only for the product of the metering of the more important ciphers, and from the spring of 1941 at Bletchley we broke most ciphers to an unprecedented extent and with an unprecedented lack of delay. And there were two reasons for that success.

First of all, alone among the governments of those years, the British Government as early as the 1920's concentrated all its cryptanalytical effort in one place which it called the Government Code and Cipher School. And at Bletchley secondly, the staff rose from about 120 in 1939 to about 7,000 at the beginning of 1944.

Of course that staff was not entirely cryptanalytical, it consisted also of an immense amount of staff used, for example, for signalling the products to commands in the rest of England or abroad. And so it wasn't entirely cryptanalytical staff - it was a very mixed staff compared with pre-war.

In addition, those men and women, recruited mainly from universities, developed methods and machinery of a sophistication hitherto undreamt of, including as you all know the first operational electronic computer which was called Colossus.

Without those advances, at least the most difficult of the ciphers, which were (although I will make some qualifying remark about this in a minute) those based on the German Enigma and those still more complex systems which Germany introduced for ciphering non-morse transmissions, would have been for all practical purposes invulnerable.

Now the value of the resulting Ultra was all the greater because the enemy states - Germany, Italy and Japan - remained unaware of the British successes.

The main reason for that was that they didn't allow for that sophistication of method and machinery which the British brought to the attack on their ciphers. They didn't allow for that when they constructed their ciphers.

Nothing very surprising in that. As I have said, the methods and machinery developed were of a sophistication hitherto unthought of.

But it still remains necessary to say that, despite that sophistication, the German belief that the ciphers would remain invulnerable was almost right, almost correct.

The ciphers nearly escaped effective exploitation.

In the case of the Enigma (which was an electro-mechanical machine) the first solutions were made by hand by mathematicians relying on German operators' errors. The German airforce was always more untidy in its signalling than the other users of the Enigma.

And for that purpose (although you will understand it better than I do) they used perforated sheets and exploited these mistakes made by German operators.

For other keys than the airforce, especially those of the army and the navy, and especially for the regular and speedy solution of those keys, it was necessary to develop an effective answering cryptanalytical machine.

That was the key in the end to the prompt decrypting of the machine cyphers.

It was a machine called The Bombe - a name originally given to it by the Poles who invented an early prototype in the 1930's. The Bombe developed in Bletchley by Turing and Welshman and Babbage - all luminaries of the Cambridge scene - was helped a little by the Polish machine, but it was infinitely more powerful, about fifteen times more powerful than the Polish machine. And it was because of the greater difficulties of dealing with the Enigma that it had to be that powerful.

But it wasn't enough to have that machinery developed. Except in the case of the airforce keys, we had to capture them before the machinery - even this Bombe machinery - could break into them.

And that is where people like myself who were non-mathematical came into the story. It was because I was in close touch with Turing, for example, that I was fully aware of what he had to have before the machine which he had developed could exercise its powers.

And I was able to arrange - with other people of course, including the navy - how to capture that. I stress that because, both in the case of the navy and of the army, and at dates which are later than we realise (I will give you the dates later), we needed in addition to this superb mathematics, which was assisted of course by superb Post Office engineering, we needed also these side assets - essentially captured material.

That was the Enigma. Now with the non-morse machine which we called Fish, the first successes were again obtained by hand methods. And those hand methods by mathematicians again exploited German operators' errors. In fact, the actual understanding of the machine theoretically (in other words as opposed to breaking it every day), the actual understanding of how it worked was obtained because the Germans went through a long series of experiments with it on the air before they brought it into operational use.

And it was these experimental transmissions which primarily were the errors which gave the entree.

But it was obvious that any regular or at all reasonably speedy decryption would be impossible if again machine methods were not developed. In particular that they would be impossible without machines because the different Fish ciphers proliferated, just like the different Enigma keys proliferated, and you were dealing with a lot of ciphers concurrently.

And so in this case, as you know, the machine was developed which came to be called Colossus.

It was of course a much more complex - it wasn't a mere electronic electro-mechanical thing - it was the first computer. It had to be like that in proportion to the fact that the Fish was far more complex than the Enigma.

Now it will be clear from what I have said that the problem wasn't merely to master the machines. The Germans recognised when they were constructing (in their view) an invulnerable set of machines, that of course in wartime they would be open to capture and therefore locally and temporarily they will be read.

But they also felt that the mere local (by which I mean reading one key instead of another key) and temporary reading (in other words that would complete your fundamental knowledge of the machine) wouldn't help you to read it regularly and daily. And they were right, without this machinery that would have been impossible.

And in particular it would be impossible because each of the Enigma and the Fish were used by the Germans as the basis not merely for one cipher each, not merely one Enigma and one Fish, but as the basis for a wide range of different ciphers, each cipher having its different key.

At one time the Germans were operating concurrently about fifty Enigmas, some in the army, some in the airforce, some in the navy, some in the railways, some in the secret service. And so you were faced not merely with understanding the machine and with breaking a key regularly, but with breaking fifty sometimes regularly at once, or as many of them as you could without delay.

And Fish similarly rose from just one link, one cipher, one key to about 22 cipher links, all quite separate except they were using the same machine. And remember that each of them - the Enigma daily and the Fish at varying interludes, usually every few days - changed the keys.

So you are on constant alert - every day you had to start again at midnight, and you had to start on perhaps 30 Enigmas or 5 Fishes and so you could see the mere load put it beyond any manual solution.

That was one reason, that in spite of their confidence which was not far from being fully justified, that was one reason why the German confidence was proved to be unfounded. The other was (perhaps it is no less important) the fact that steps were taken to avoid arousing enemy suspicion.

The British imposed strict secrecy of course on the Ultra production process. Strict regulations about its distribution - who should be indoctrinated - strict regulations against carelessness by users when using it.

Those regulations were pretty effective. There were from time to time cases in the war where the Germans did sufficiently suspect to have an enquiry. There were cases when the Italians suspected and advised the Germans to have an enquiry.

I ought to say that everything I have been saying about the complex nature of the attack on the ciphers hardly applied to the Italian ciphers - and this is where I am going to bring my ironical remark in about ciphers which will interest you people as machinery experts.

The Italians only ran one machine and it was a baby really compared with the Enigma. It was a machine built by a firm called Hagelin (we called it C-38). The American armed forces used it occasionally, but it was easily broken. We broke it. It didn't come into use until the beginning of '41 and we broke it by June '41.

It was a very valuable cipher for shipping in relation to North African operations but it wasn't a cryptanalytical problem of the kind I have been describing in the case of the German ciphers.

Ironically the Italians, except for that one cipher and also for one they used for their diplomats, didn't use machines. They used book ciphers, and ironically we couldn't read the Italian book ciphers for the army, the navy and the airforce after they brought new ones in between June and November 1940 preparatory to or as a consequence of their own entry into the war.

Book ciphers proved to be invulnerable when the machinery proved not to be invulnerable!

And as I say the Italians occasionally, who rather looked down on machine ciphers, warned the Germans that they thought that there was evidence that the way the allies behaved suggested that maybe they were reading the German ciphers. And the Germans said 'Pooh, pooh, we are alright!' Apart from occasional suspicions, those precautions I described, as used by the Allies, worked.

They were wholly justifiable ones. Any confirmation reaching the Germans that this whiff of suspicion that this system that they had constructed wasn't safe, would have led to not easy but not impossible steps to render it safe.

But of course the precautions complicated the task of establishing the value that Ultra had in the war.

Contemporary reports and the memoirs and histories that have been published before the records about Ultra became available, of course allow for, incorporate, the contribution Ultra made to decisions and the course of events, but they don't acknowledge it. Because either the writers of the reports and the memoirs didn't know about it, or they were not able to mention it.

So that historians now have to identify that contribution from the written records about the war and it is a straightforward job to do that now that Ultra is available. You can see - we know what Ultra went to what commands, we know what time it arrived, we know what other intelligence they had at the time the Ultra arrived, we know what decisions and orders followed from its arrival, and frequently we have discussions on record about what they thought about what they ought to do about it before they reached their decisions.

It is not enough to establish accurately the availability of the Ultra and to reach reasonable conclusions about its influence on British and American assessments and decisions. You have also got to consider the consequences of those assessments and decisions on the war.

Let me give an example of the distinction. Once you have identified the Ultra (which you now can from the decrypts in the Public Record Office) you can see pretty clearly (if you have also got the record of the war) that Ultra was the main reason why the British were able to reduce the depredations of the U- Boats in the Atlantic in the second half of 1941.

But what was the value of that effect in the North Atlantic in that second half of 1941 on the course of the war? What was the consequence of that use of Ultra on the course of the war? And those effects too are already incorporated into the record, which shows that the U-Boats were defeated in the North Atlantic in the second half of 1941.

Of course in order to assess the true significance of Ultra we have got to assume that it didn't exist in the North Atlantic at that time. We have got to strip it out of the record in order to get its true significance into focus.

This is what historians call counter-factual history. To calculate something assuming that some factors in it didn't exist. And I am sure it is a process well known to mathematicians and other people like yourselves.

But it is still the case that there is a great deal of danger in using counter-factual history unless you use it very carefully. For example it is very common among historians to use counter-factual history either from a desire to shock or because the user in question hasn't got any judgement. And you have therefore got to use it in relation to the possibilities that were practically available in the circumstances that you are considering.

There is no danger whatever in reconstructing the course of the war on the assumption that Ultra hadn't existed.

As I have said the story of its acquisition is of near legendary, even science fiction proportions, because it might so easily not have taken place. You are not making a huge assumption when you start playing with the record of the war on the basis that it hadn't been solved, it hadn't been obtained.

It was by no means fortuitous or miraculous. It was the consequence of forces deliberately brought together to solve it. But it was far from being inevitable that the forces would succeed. The proposition that we might have had to fight the war without Ultra is a reasonable and necessary element in the assessment of its true significance.

On the other hand if you apply counter-factual history and use this proposition that Ultra might not have existed, you are undertaking a pretty bold enterprise in hypothesis and speculation and you must control that exercise by a constant reference to the straightforward facts about what Ultra actually did do.

If you apply that check, then I think we can draw two pretty sound conclusions. First of all, though we did obtain it in such amounts, amounts rising to 2,000 of those Italian Hagelin decrypts a day at the peak of the Mediterranean War and to 30,000 a month rising to 90,000 a month of Enigma and Fish decrypts combined - that is a very big number of decrypts. It is still the case that those volumes and the speed with which they were got out were not fully established until the second half of 1941.

Up 'till June '41 the successes were confined to decrypts of the German airforce Enigma and some of the Italian book ciphers which were quite readable before Italy came into the war and for a month or two afterwards.

Those helped to produce isolated allied successes like the Battle of Matapan when we defeated the Italian fleet, and wouldn't have done so but for a few Enigma and Italian signals which gave enough warning to the British Alexandria fleet.

The distances in the Mediterranean are such that unless you have got some notice you can't cover the thousand miles or the seven hundred and fifty miles.

So Matapan was one success. The sinking of the Bismark was another. Again I am speaking of the period before June '41. She was sunk in May '41 just before the turn. The defeat of the Italians in East Africa and in North Africa. Those were Allied successes, but they were slightly isolated successes.

Again in the same period Ultra did something to mitigate British disasters. It greatly assisted the British forces that were sent to Greece, to retreat without serious loss when it become obvious that they couldn't hold a line against the scale of the German invasion.

It gave us - here was another disaster - all the information required to destroy the German attack on Crete. We didn't destroy the attack but we made it an extremely damaging exercise for the Germans, which was done because the Ultra signals were so complete.

Some people think we should have prevented or destroyed the invasion - an air landing invasion. In fact Bletchley Park felt very strongly for the first time in the war that its product had not been used properly in the case of the Crete invasion. I think possibly that we were wrong now that we can see the evidence in more detail, but at least it helped to make it a disastrous operation for the Germans even though they actually got Crete as a consequence.

And so in all that story you can see that the British survived the war with little benefit from Intelligence until the Germans invaded Soviet Russia. And since Soviet Russia survived the German invasion, and that invasion was followed by the entry of the United States in December '41, we can safely conclude that Germany was going to be defeated in the long run, even if the enormous expansion of Ultra from the summer of 1941 had not from that date given the Allies this massive superiority in Intelligence which they retained until the end of the war.

They were hardly ever rivalled by Axis success in reading our ciphers. There were two major exceptions to the lack of success by the Axis against Allied ciphers. One was that they did have some success in reading a British naval cipher which was for a longish time also shared with the American navy in relation to convoy escorting.

They were successful in reading that for a long period from 1940 to the end of '42. And the other was that they didn't exactly capture but they managed to extract of copy of the cipher that was being used by the American Military Attache in Cairo for a period when Rommel was at his most dangerous. And from that too the Germans obtained some great advantage.

But generally speaking, except possibly in relation to the convoy cipher, there was never any great cryptanalytical rivalry. The Germans were completely outclassed in terms of Ultra. The Italians also made very little progress against any important allied cipher.

In June 1941 however, (we survived 'till then with very little value from the Ultra), the end of the war still four years away. And that is such a length of time that we might be tempted to jump to the other conclusion and say that far from producing by itself on its own the defeat of the Axis, it made only a marginal contribution to it.

Here we are, we start getting this Ultra coming onto stream in June '41 as opposed to the slight trickle before that date, and yet you have still got four years of war. How can it have made much difference?

But that second conclusion can I think be as firmly dismissed as the one I have been discussing about how Ultra didn't really win the war.

The second real conclusion that stands out is that Ultra was decisive in shortening the war from the time, beginning in the summer of 1941, the cryptanalytical successes were extended from the German airforce Enigma keys to the Enigmas used by the navy and the army and the secret service, to the non-morse ciphers of the German High Command which came on stream in mid 1941, and to a new Italian machine cipher, the one I have mentioned which also was brought into force beginning of '41 and broken in the summer of '41. And to the ciphers of the Italian and German and especially Japanese Embassies.

The Japanese Embassies in Europe were in the second half of the war to prove of immense Intelligence value because they were repeating back to Tokyo their versions of German assessments and their knowledge of German intentions. They were almost as valuable on some subjects (like for example the Normandy Landings) as were the direct Ultra from the German horse's mouth.

From the moment we began that expansion you can see that the influence is continuous. I have spoken of the amount of Ultra there was. The lack of delay, the fact that they were obtained with very little delay was equally important. After all, one of the crucial characteristics of Intelligence is that to be useful it must be quick.

In the case of the Enigmas we didn't exactly reach a position in which the new keys, having come into force at midnight, were broken by breakfast, but of, shall we say, twenty, twenty five Enigmas running concurrently (the number varied according to different stages of the war), we would be reading twenty to twenty five at most times. Of that twenty to twenty five the ones to which highest priority was given on the limited number of Bombes available would be out by breakfast. Which meant that the whole of the rest of that 24 hours' signals from the moment you broke the key for the day, the setting for the day, would be read instantaneously, as soon as the message was intercepted it would be decrypted.

Fish was a bit slower. It didn't change daily like the Enigma. It varied, on different links it changed with different frequency. The average was that it changed about once every five or six days - the setting of the keys changed every five or six days.

Again the number we read varied from time to time but from the end of '42 when Fish on the German side got going strongly, we were generally reading four or five Fish links at any one time.

Generally we were reading them about seven, six, five days late - after their transmission. That didn't matter with Fish (at least it didn't matter so much as it would have done with Enigma) because, whereas the Enigma like that Italian machine was used for what you might call operational purposes below army level for something that was happening tomorrow or happening today, Fish was reserved for communications between the highest commands of the German Armed Forces. Between Berlin and the army groups or the armies. And then never lower than armies. It was a system that increasingly replaced the landline transmissions between Berlin and Kesselring in Rome and Von Rundstedt who was commander in the west in Paris by 1943.

They were on landlines normally but gradually with Fish being perfected as they thought and with landlines being damaged by bombing they put more onto the air.

So Fish was carrying Intelligence of a character that didn't really depend for its value on immediacy. It would carry long term estimates, or it would carry prolonged discussions between German Headquarters on the Russian Front or in Italy and Berlin about what was the best thing to do next. So you didn't have the immediacy requirement there as you did with the Enigma.

Speaking on the whole then we can see the fact that we were getting Ultra in the amounts I spoke of and with the speed that I emphasised as being a very important characteristic of valuable Intelligence. It was no use having Enigma a week late, and it wouldn't be much use having Fish more than a month late.

If you had that amount of decrypts with that small amount of delay, it would, I think, on the face of it, be surprising if Ultra hadn't contributed to the very considerable shortening of the war, given the fact that on the other side the enemy is blind and his Intelligence is increasingly deteriorating because of the Allied possession of the superiority in Intelligence.

I will give you an example of that. We read all the Enigma signals of the German Abwehr which meant that we captured every spy that arrived in the United Kingdom by having advance knowledge of his arrival. Which meant that we could turn such as we needed and use them to send messages we wanted the Abwehr to receive, and monitor the reception and the reaction of the Abwehr. All that signal Intelligence underlay the effective use of what was called the Doublecross Operation for the purposes both of stopping German reception of Intelligence (other than false Intelligence) and also of creating deception by sending them false Intelligence.

So given that they were so blind and we were getting this increasing amount with less and less delay, it would be surprising if it hadn't, from the middle of '41, contributed pretty appreciably to the difficulties of the enemy and to the accurate appreciations of the Allies.

Now the question remains how much did it shorten the war, leaving aside the contribution made to the campaigns in the Far East on which the necessary work hasn't been done yet. My own conclusion is that it shortened the war by not less that two years and probably by four years - that is the war in the Atlantic, the Mediterranean and Europe.

The detailed answer for those theatres begins in the Mediterranean. There, in the autumn of 1941 against Rommel it turned almost certain defeat into a stalemate. If not then, then certainly in the summer of 1941 after Rommel had returned to the Egyptian frontier, it made a decisive contribution to keeping him out of Egypt between his victory at the Battle of Gazala in 1942 and the British getting ready for their own victory at El Alamein.

It did this chiefly by killing off his seaborne supplies. Both the Italian machine cipher and the airforce Enigma and a bit of naval Enigma contributed decisively to starving Rommel of fuel and replacement hardware and ammunition.

Without that, the commander of our own forces at the time, General Auchinleck, concluded that Rommel would have got through to Egypt.

As you know at that time the Allies themselves were landing in North West Africa. If they had lost Egypt they might have abandoned the operation against North West Africa, especially as they would also have lost Malta if Egypt went, and decided to alter their strategy (we have to allow for this possibility) and go back and concentrate on the North Sea and the direct Second Front.

Now if they had stayed in the Mediterranean it would have taken them a least a year longer than it actually took them from Tunis and from the Western Desert to complete the conquest of North Africa and open the Mediterranean. That was successfully achieved in May '43.

It wouldn't have been achieved in less than a year beyond that, if we had gone on in spite of the loss of Egypt trying to do it. It wouldn't have been achieved in time to do the Normandy landings in 1944.

If they had abandoned the idea of re-conquering North Africa, the most probable course would have been in fact what the Americans had always wanted to do, to do the cross Channel invasion more quickly than in fact occurred. It in fact occurred in June '44. They would have turned back and done that straight away, that was their obvious alternative.

What would have been the prospect for that undertaking if Ultra hadn't become available against the U-Boats in June 1941 and radically reduced their successes against the convoys.

We know that in that second half of 1941 their shipping successes were cut back to 120,000 tons a month average. That has to be compared not with the monthly average of 280,000 tons a months in the four months before June '41 but with the sinkings they would have achieved with their greater number of U-Boats.

It has been calculated that the Ultra saved about one and half million tons in September, October, November and December '41.

And even if Britain's essential imports had not without that reduction been reduced to a dangerously low level, the intermission that provided was invaluable in enabling the British to build up reserves in merchant shipping and develop anti-submarine defences.

So that when the U-Boats returned to the Atlantic after their first defeat (they did that in the autumn of 1942), they had been delayed in making a decisive thrust for more than a year. Now when they returned they had been supplied with an advanced Enigma, one that instead of using three wheels concurrently used four wheels, which as you can see noticeably increased the mathematical difficulties of solving the key.

In fact Bletchley couldn't solve it from February to December 1942. Mercifully for us (though not for the Americans) most of the U-Boats were on the Atlantic American coast at that time, but as they came back to the North Atlantic convoys they were still using this cipher and they brought about another crisis in the Atlantic.

It again was the Ultra which brought them under control. The figures of sinkings of Allied shipping reached the highest in the war in March '43. They had been brought down by May '43 to lower proportions than ever before in the war as a result of this return of Ultra to the scene.

And so you can see that the problem of undertaking the Normandy landings if those two defeats and controls of the U-Boats hadn't occurred would have been very pronounced.

Then there was the contribution of Enigma to the Normandy Landings themselves (I can't go into detail and will answer questions if you need). I think it is no exaggeration to say that even if the U-Boats had prevented it from being attempted only until '45, we would have found it an infinitely more difficult operation to do than in 1944. The Germans would have completed the Atlantic defences, they would be bombarding Britain with 'V' weapons on a massive scale, all of which was in the event cut off by the '44 Landings. And they would have had a much bigger Panzer Army to deal with the problems.

My own calculation is we wouldn't in fact have been able to do the Normandy Landings, even if we had left the Mediterranean aside, until at the earliest 1946, probably a bit later. It would have then taken much longer to break through in France and Germany than it did in fact take, which was a year from '44. And altogether therefore the war would have been something like two years longer, perhaps three years longer, possibly four years longer than it was.

I am sorry I have exceeded my length of time but I hope you will forgive me, and I will do what I can to answer questions.

Q. Would we have won the war without Ultra?

My own view is that given that the Soviets survived the German attack and the Americans came in as they did, the combined forces of Russia, America and the British would eventually have won the war. The long term relative strengths of Germany and those three counties were such that Germany was bound to loose in the end. But how lengthily and with what damage and destruction we should have succeeded I don't know. I think we would have won but it would have been a long and much more brutal and destructive war.

Q. Was Bletchley involved at all in cryptanalysis of the Russian theatre?

We read a large amount of German signals from the Russian front, but no work was done against Soviet signals after Germany invaded Russia, on account of the high priority given to Axis signals. On the other hand, co-operation with the Soviets was never as close as it was with the USA.

Of course when the Americans came into the war in December '41 we had already begun some development of a cryptanalytical partnership with them, and when they came into the war that partnership became almost so complete as to constitute a single joint cryptanalytical effort. Of course that effort involved division of labour and the division of labour is much directed by the interception facilities. For example, except for the Atlantic traffic the American coast couldn't intercept European, German and Italian signals. That was all being intercepted in the UK. Obvious solution - UK concentrates on decrypting, on cryptanalysis against German and Italian. America which can intercept the Pacific from the Pacific and also has headquarters in Brisbane and various places in the Pacific - America concentrates of working on the Japanese.

But there are overlaps. For example we have a cryptanalytical annexe at Bletchley, we have it in Singapore, it moved to Hong Kong, it moved to Ceylon, and from there it pitches in its bit by serving the decrypts direct to the American Headquarters. Similarly because the U-Boat traffic can be heard both in America and in Britain, the two sides - Bletchley and the American Navy - swopped keys. They have got a direct line. They say 'we will take 4th June, you take tomorrow 5th June,' and so they split the keys and swopped solutions. So there was an almost total amalgamation of resources and a logical division of labour.

Q. Is it not the case that the arrival of the atom bomb in 1945 would have bought a quicker solution?

This is a problem because strict, sensible, proper counter-factual history can't really take into account something like that. It is speculation. But of course if my scenario is right and the war was still struggling on and we had the bomb which presumably we would still have had, the problem of whether to drop it on Germany would have arisen. And in some respects the dropping of it on Germany would be more justified than the dropping of it on Japan because Japan was visibly on her knees when we dropped it on her, but in my scenario Germany would have been far from on her knees. So yes the prospects of it being dropped as the solution are quite high. I would mention it in a speculative scenario.

Q. How closely did Bletchley work with the Russians on decryption?

It couldn't be as close as the collaboration I have described with the Americans for a variety of reasons. One is of course that there just hadn't been the close relationship between the two countries that existed historically between the British and the Americans. The other was that when we actually broke the ciphers - Enigma in the first instance, but Fish later - that were relevant to the Eastern Front, they were coming in to us at a time when it was uncertain whether Russia would survive. And then later on when Russia had survived and we were reading more ciphers both Fish and Enigma from the Eastern Front, there was the problem that we knew from the Enigma that the Germans were reading Russian ciphers, so that if they had too much Enigma intelligence in their ciphers you see the security risk was extremely high. Then fourthly the Russians were not collaborative. They wanted any intelligence we supplied but they wouldn't give any in return. Not that they had much Sigint, but they had a lot of other Intelligence.

The answer to your question is with all those difficulties we couldn't have so close a collaboration with the Russians as we had with Washington, but we started sending them a summary of signal intelligence a week after they were attacked by the Germans in '41. We sent it via the British Military Mission in Moscow where there were people to hand it over to the Russian General Staff.

We had to have a cover for it, had to explain to them that this is the horse's mouth but it is coming to us (this is the kind of cover we used) it is coming to us from very high ranking German officers who are slipping the news to us through Berne or somewhere like that, and we are getting it quickly because we have got pretty direct connections with Switzerland.

A steady stream of information about German intentions and dispositions - Airforce and Army on the Eastern Front - were sent to them. They were interrupted from time to time when the Russians were being particularly beastly. For example at the top of Russia, Murmansk at the Kola Inlet where all the convoys taking arms to Russia and supplies were going, we had to keep seamen, sailors, both to man the Allied facilities, unloading facilities - of course the Russians were there too but we had to keep some British sailors there. And then we persuaded the Russians to let us have an Intercept station there because half of the traffic around the top of the North Cape was difficult to intercept even in Northern Scotland.

And of course we covered the risk that they would suspect that we were reading Enigma or that they would do more than suspect that, by saying that the value of the traffic to us was that it enabled us, by traffic analysis, to judge the German reactions to the movements of the convoys. So we had this little intercept station and then the Russians locked them all up because they thought we were spying on them, so you had all sorts of little rows with them like that. From time to time when it wasn't vital we did say if you don't behave better than this we wont send you your daily summary. And we stopped it for a short time, then we started again. But it had to be of that character - the collaboration.

Q. Is there scope for counter-factual historians studying the siege of Leningrad - if they had had access to the Ultra information that you could have given them.

Again you have to bear in mind that there were problems. For example, one of the areas in which we found it extremely difficult to intercept German signals because of radio conditions or atmosphere conditions or whatever it is, was the North Cape; and the other was the Leningrad area. It was very difficult to intercept from the Leningrad area because whatever frequency they were using relative to the distances and the ionosphere we never could cover the Leningrad area properly. Caucaucus on the other hand, Central Front, we could hear then as clear as a bell.

Q. If the collaboration had been as close as with the Americans . . .

It would have been an advantage if it had been as close as with the Americans, it is quite true. But on the other hand the risks which I briefly portrayed were quite considerable. And we did our best to make sure that they knew about all the important forthcoming development. Don't forget they had very good intelligence of their own, not primarily Sigint but they had very good air reconnaissance and air superiority after a certain time, and they had an enormous espionage system behind the German lines. So they weren't without information. But we did do our best to make sure that they got crucial early notice whenever we got it ourselves.

It was a big dilemma and one that was fought about. Churchill wanted to risk it and let them have more. Naturally the Ultra authorities didn't want to risk it because everything hangs on it you see, so there was a tussle all the time about how much to send.

Q. The was a programme recently on Kursk - one might say that a Russian counter-factual historian would say that if we didn't have the Ultra which we got in various ways, then we wouldn't have been able to win the battle of Kursk and Hitler would have been able to carve up Russia. This is perhaps another case . . .

Another case. Stalingrad of course is another one. Those two battles were crucial, especially Stalingrad. Again it wasn't only through us they were getting . . . we did give them the central facts in advance of Kursk. But as we now know, we didn't know at the time, the one single Russian agent in Bletchley was at that time (just that short period of time before and after Kursk in '43) actually giving them decrypts through the Russian Embassy in London. So all sorts of complications about the story. He didn't know that they were getting the supply from London officially, and we didn't know that he was sending the decrypts unofficially. Quite a complex problem!

Q. Did they never figure out that this was coming from decrypts?

We are never quite clear. Certainly when this man at Bletchley who only surfaced after the war - the secret about him only surfaced after the war - they knew that what they were getting from him was decrypts. They must then have known that our summaries were decrypts. But that didn't alter our practice because we didn't know that he was sending them the decrypts.

Q. How was the Ultra Information disguised so that the Germans couldn't work out that you were decrypting them?

How did we disguise what we had got you mean?

Q. How did you disguise, for example, that a particular submarine was going through a particular area? How could you disguise it so that it wasn't obvious that you'd intercepted it?

Let me give you an example of how we took the precautions, using it without on the other hand giving grounds for suspicion to the other side. The most dramatic example comes from the Mediterranean where we sank at two or three stages in the war something from 40% to 60% of every ship that left the north shore of the Mediterranean for North Africa. 60% of the shipping was sunk, for example, just before the Battle of Alamein and again just before Gazala when Rommel was stopped.

Every one of those ships before it was attacked and sunk had to be sighted by a British aeroplane or submarine which had been put in a position in which it would sight it without it knowing that it had been put in that position, and had made a sighting signal which the Germans and the Italians had intercepted. That was the standard procedure. As a consequence of that the Germans and the Italians assumed that we had 400 submarines whereas we had 25. And they assumed that we had a huge reconnaissance airforce on Malta, whereas we had three aeroplanes!

But solemnly that procedure had to be followed by the commanders. When they in their little centre in Cairo or, as it was later on Algiers, said we can't sink all those seventeen ships today, which five are we going to take first and which five will we take second, when they were doing this they had to arrange that procedure before they hit a single ship.

Similar precautions were taken in the Atlantic, but there the problem was different. That is why the Germans got most suspicious about the Atlantic. The great feature there was that the Enigma was used in the first instance not to fight the U- Boats but to evade them. And the problem was how could you evade them without their noticing. You have a situation on the graph in which the number of U-Boats at sea in the Atlantic is going up, and the number of convoys they see is going down!

How do you cover that? We did cover it but it was done by a different system from what I have just described in the Mediterranean. We let captured Germans, people we had captured from U-Boats write home from prison camp and we instructed our people when interrogated by Germans - our pilots for example - to propagate the view that we had absolutely miraculous radar which could detect a U-Boat even if it was submerged from hundreds of miles. And the Germans believed it.

They had an enquiry saying 'surely it must be possible that it is the Enigma that isn't safe.' And the cipher men come back and say 'it can't be the Enigma.' So somebody gets up and says 'well, it must be this bloody radar that we have heard about.' And so they decided. But you see different solutions had to be adopted for each particular situation. But these were the kind of precautions that were taken I think with great success. I mean they never really did tumble to the idea that it was unsafe, which is pretty marvellous really.