How to Build a Creativity Culture II

Phase II: Open - Action - Thinking

Washington DC June 12, 2023

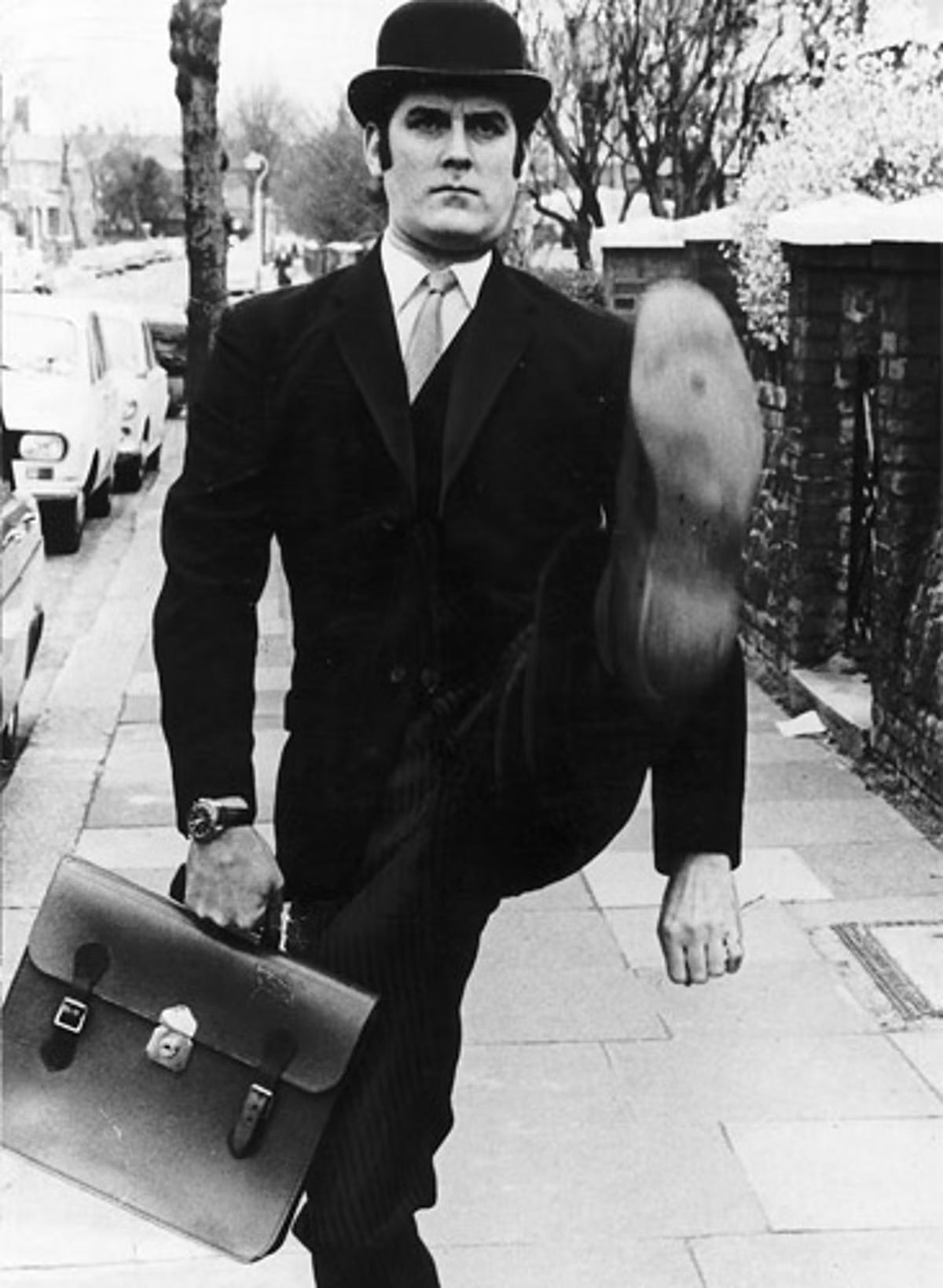

You may know John Cleese as a member of the comedy sensation, Monty Python. You likely do not know that he is one of the finest strategic thinkers of the 20th century. Cleese has been living a double life for decades. It is to his secret life as the unstudied and unappreciated Clausewitz of military innovation that we turn today. John Cleese is not a British Army General. Nevertheless, he would make a very fine one, not because he mastered the most athletic goose-step in world history that is much admired in Pyongyang, but because he knows how to think. As your first thought was “oxymoron”, you are now obliged to keep reading.

The Cleese military motto is “Who thinks, wins”. That is, if he knew the applicability of his ideas to the military world. As it is, MILabs is just putting words in his mouth - good words. He wont mind. Cleese has devised a system of thinking that not just tolerates, but prevails in, conditions of volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity. What we call VUCA, Cleese calls “life”. While we would tend to agree with his characterization of life, we must confine our focus to the unique part of the human experience of life relating to death. Or more specifically, the use of organized violence by the state for the purpose of achieving political outcomes. Otherwise known as WAR.

Cleese has been running a side hustle as a published lay-psychologist for decades including multiple stints as a “Professor of Practice” at Cornell University. Both individually, and together with the late Dr Robin Skinner (a WWII RAF Mosquito pilot and professor at the London Institute of Psychiatry), Cleese has authored a number of books on subjects of critical importance to the work and interests of the Military Innovation Lab.

There are many misperceptions about creativity and innovation. For example, that they are innate to artistic people like Cleese and unobtainable by the rest of us. Cleese disagrees. He advises

Another myth is that creativity is something you have to be born with. That isn’t the case. Anyone can be creative. Wherever you can find a way of doing things that is better than what has been done before, you are being creative.

Or as a sign on the hatch of a ready room in a carrier read “if it’s stupid and it works, it’s not stupid”.

This article will explore Cleese’s ideas in some detail. His insights are both powerful in the abstract and especially useful in application. Indeed, he outlines specific ways to set the conditions to think creatively. Given his artistic accomplishments it is hard to argue against listening to what he has to say. As the article unfolds it will be possible to see linkages between Cleese’s method and larger issues in philosophy and science and how they connect to the art of war. Most military staff’s operate in the red/orange zone of the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy below. Cleese provides a road map to the yellow zone.

Notes: Unless other citations are presented, all Cleese quotes are from a talk he gave in London in 1991.1

Critical Thinking, Innovation and Creativity

How are they different? A study on innovation conducted at Cambridge University provides these excellent definitions and explanations. It is worth remembering at this point that warfare is a learning activity. The principles and methods of andragogy are precisely the same as those needed to run a military staff.2

Critical thinking is the ability to identify, analyse and evaluate situations, ideas and information to come up with responses and solutions. Creativity is the ability to imagine new ways of solving problems, approaching challenges, answering questions or creating products.

Innovation can be broadly thought of as new ideas, new ways of looking at things, new methods or products that have value. Innovation contains the idea of output, of actually producing or doing something differently, making something happen or implementing something new. Innovation almost always involves hard work; persistence and perseverance are necessary as many good ideas never get followed through and developed.

Creativity is an active process necessarily involved in innovation. It is a learning habit that requires skill as well as specific understanding of the contexts in which creativity is being applied. The creative process is at the heart of innovation and often the words are used interchangeably.

Ferrari, A., Cachia, C. & Punie, Y. (2009). Innovation and creativity in education and training in the EU member states: Fostering creative learning and supporting innovative teaching. European Commission Joint Research Centre.

Playtime!

In reviewing books, articles and talks on innovation, in the military, business or technology, it is stunning how often the word “play” appears. It is the crimson thread running through every work on innovation. The association of playfulness, laughter, and humor to thinking about the orchestration of death, might be hard to grasp at first. Yet military innovation relies on being able to play. After all, “Kriegsspiel” or war game, is the first testing ground of new military ideas. The German “spielen” means “play”.

It may be counterintuitive to think of play as essential when talking about matters of life or death. When feminist scholar Carol Cohen spent a year with nuclear strategic planners, she was part intrigued and part horrified by how her colleagues addressed their work.

As a newcomer to the world of defense analysts, I was continually startled by likable and admirable men, by their gallows humor, by the bloodcurdling casualness with which they regularly blew up the world while standing and chatting over the coffee3

Nuclear warfare is filled with taboos, human extinction, for example. Humor does not trivialize the subject as some might assume. Instead it provides a vent for the stress of the necessary work of understanding nuclear warfare in order to create ways to prevent it. It also provides a mask to shield from the horror of thinking the unthinkable. There is a lot of irony in nuclear warfare, where attacking an enemy becomes suicide. It is the study of counterintuitive disconnects. That might be the definition of irony. The juxtaposition of well known concepts that yield an unexpected outcome is the definition of humor, and one pathway to creativity:

In a joke the laugh comes at a moment when you connect two different frameworks of reference in a new way. Having an idea, a new idea is exactly the same thing. It's connecting to hitherto separate ideas in a way that generates new meaning.

Be serious - not solemn

Military culture is characterized by a rigidly structured hierarchical world built on rank and status, where authority is derived from position and time served. The values of the university and cutting edge tech - curiosity, imagination, and intellectual novelty - are not a priority and in some instances may be seen as a threat.

Military culture reveres and rewards physical courage for taking life-threatening risks. It does not have a tradition of revering or rewarding moral courage for taking career-threatening risks (with new ideas). At the tactical level, particularly under the sound of the guns, trying something different, even disobeying orders, can be considered useful or even valorous - particularly if it works. The reverse is true at the strategic level and/or “in garrison” because the risk of failure is much greater. The status quo fallacy is similar to the sunk cost fallacy - both reinforces aversion to change even if it appears to hold more promise of future success. It also reflects the priority placed in Headquarters organizations on obedience to rank and seniority compared to thinking differently.

This is the bureaucracy - innovation divide. Or as MILab explained in the introduction to the purpose of the Lab - “the fault line between control and creativity”. As outlined in the brief MILab introduction below, both control and creativity are needed in war and warfare. There is an inevitable tension between these opposites. Typically control drowns out creativity due to the character of military culture. One of the purposes of MILab is to advocate for how some equilibrium might be restored to this overwhelming imbalance.

The national security world is naturally a place of great seriousness. Cleese insists that there is an important distinction between seriousness and solemnity. Understanding this distinction empowers us to expose serious issues to play, free from criticism that we are trivializing significant matters.

He adds an arguably more important insight: some people fear humor and that is a sign they are not suited to creative solutions to risk. The psychologist in Cleese cautions against those who take themselves, rather than the issues, seriously. Self importance is a red flag with important implications for ways and means of achieving change.

There is a difference between serious and solemn. Serious issues can be addressed using humor. I don't know what [solemnity] is for. What is the point of it? The two most beautiful memorial services that I've ever attended both had a lot of humor and it somehow freed us all and made the services inspiring and cathartic.

Solemnity serves pomposity. The self-important always know at some level of their consciousness that their egotism is going to be punctured by humor. That's why they see it as a threat, and so dishonestly pretend that their deficiency makes their views more substantial, when it only makes them feel bigger.

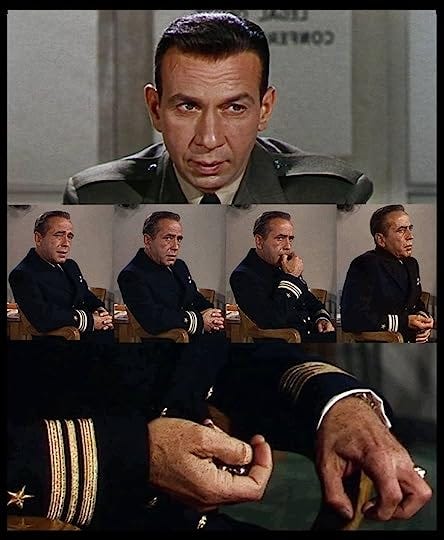

The cardinal rule of military leadership is that regardless of the cause, “the captain of the ship is always responsible” no matter what happens. Trying something new means the status quo has failed. By inference, those responsible for the status quo have failed. Any weakness or failure is therefore resident in the person of the leader. The cardinal rule is designed to spur leaders to make every effort to ensure their team is competent and can anticipate challenges in order to prevent them from becoming crises or failure. Accordingly, this rule incentivizes a mindset of constant improvement in leaders who have confidence in themselves and their teams.

Alternatively, the cardinal leadership rule can foster timidity, risk aversion, distrust, resentment, and politicization of the workplace. Any deviation from the status quo is treated as an existential personal threat by weak leaders. Suggestions for improvement are internalized as a personal attack to be resisted at all costs because any change would be an admission of personal failure. Weak leaders are driven by ego. They are “fake it till you make it” types who never made it. Doing so would require self awareness, sense-making and adaptation skills. In other words, the capacity to learn. Instead of seeing their command as an organism that is constantly evolving in a ceaselessly changing environment - anticipating, responding, preventing and deterring - they see only chaos demanding simple solutions based in rigidity and order.

This is why authoritarians cannot stand satire. One of the great traditions of US politics is the annual White House correspondents dinner (aka “the Nerd Ball”). The most powerful man in the world is openly ridiculed for hours on end. To his face. In front of millions. What could be more healthy?

Almost every President since Calvin Coolidge (1924) has attended (with the occasional exception due to global crisis and a handful who feared the occasion - Nixon, Carter, Trump). Even Ronald Regan called in from his hospital bed when he was recovering from an assassination attempt and joked about what it was like to get shot. That’s a leader!

Open for Innovation

Cleese and Skinner describe alternating between two modes of thinking - Open and Closed.4 Outside of psychology, individuals or groups rarely actively think about how they do the work of thinking.5 Because of this, the closed mode often becomes the default mode of thinking. To avoid this pitfall, the authors propose a conscious understanding of both Open and Closed Mode thinking and the role they play in how we approach intellectual challenges. Unpacking this approach yields results in how we think about, plan, and do warfare to achieve the aims of war.

In Cleese’s usage, ‘Closed Mode’ is descriptive, not pejorative. For a military audience, the potential for association of ‘closed mode’ with ‘closed mindedness’ is a counter-productive and all too easy trap to fall into. Consequently, we will adapt the terminology thus: ‘Open Mode’ and ‘Action Mode’. This removes potential for unnecessary misunderstanding or friction. It also neatly fits the military world where “action officers” on military staff’s implement the decisions of commanders within the parameters set by doctrine.

In the Open Mode there is freedom to be creative, to think the unthinkable, to propose ideas, then challenge and deliberate them until an understanding is achieved. It is unrestricted thinking that takes nothing for granted. It seeks to cross-examine all assumptions, contexts, hypotheses, and lines of argument, looking for anomalies, irregularities, faults and counters. Open mode thinking asks “why”. Answering the “why” accurately, enables the creation of a strategy - that MILab defines as “a plan(s), using resources, to achieve an objective”.6

Once a decision has been made, it is necessary to shift to the Action Mode that facilitates implementation of plans. Action mode thinking provides a solution to practicalities: “how”, “when”, “where”, and “who”. In modern war, Action Mode thinking is incredibly hard, complex, and energy/resource intensive. Its span is rarely limited to one unit, time or place. Military doctrine is designed to align all closed mode actions into a coherent whole.

Once a strategy and its associated scheme of plans is implemented, it is necessary to evaluate progress toward achieving the objective. This necessitates a return to the Open Mode to collect data about implementation and critically evaluate it. A new adjusted ‘hypothesis’ for action results, and the cycle is repeated.

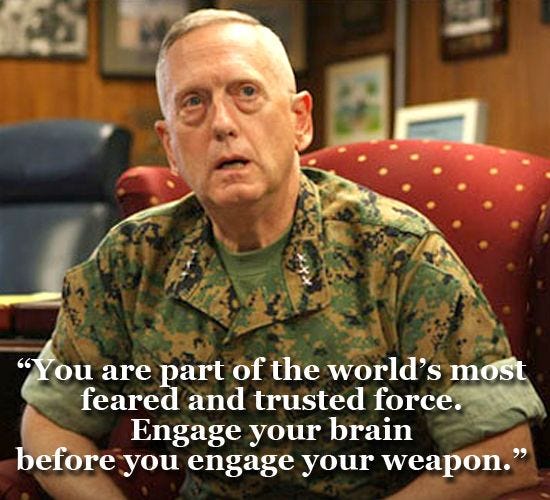

General Mattis one said “doctrine is the last refuge of the unimaginative.” He did not mean the military should abandon all doctrine and have a free for all in the battlespace. Mattis was walking the line between doctrine and dogma. He was lamenting the tendency of some to avoid open mode thinking in the plans phase and the exercise of initiative in the action phase. Here dogma masquerades as doctrine, and is used as a crutch (or cudgel) by weak leaders to avoid creativity/initiative.

Confident leaders encourage subordinate participation in open mode thinking. Involvement in the creation of the reasoning behind the plans enables subordinates to understand (or share) the commanders intent, thereby preparing them to adapt to a fluid situation as it unfolds, rather than waiting on constant micro managing from above. This is called “Mission Command” and it is what sets western militaries apart from their opponents in autocratic and authoritarian regimes.

Recall for example, that the Chinese military is an arm of the CCP. It is the “Army of the party”, not an instrument of state power as it is in Western democracies. PLA members all swear allegiance to Xi as leader of the Party. In America, the Army is a national institution that swears allegiance to the Constitution and is guided by law. If it were like the PLA, members would swear allegiance to the leader of political party in a one party state. The command and control of the PLA is built on disunity of command - another cardinal point of failure. Political commissars and military commanders are co-equal leaders, each with very different agendas. The PLA also has a weak to nonexistent NCO corps. Combined, this structure and culture encourages the very worst of the pitfalls or negative tendencies of military culture noted above. Even the senior most operational commander has to check his decisions with his political officer, who in turn will seek permission from the party. Such a system extinguishes any possibility of independent action based on a commanders intent because the commander is not allowed to have one! Only the party commands, and how its intent is derived is unknown to all but the inner-most politburo insiders. No general, let alone an NCO, is going to exercise initiative in such a system.7

Open Mode thinking

Recall that control (bureaucracy) and creativity (innovation) are needed in war and warfare. Action mode and open mode thinking are their operating systems. In sum, bureaucracy is the exercise of control through action mode thinking; and innovation is the stimulation of creativity through open mode thinking. We will focus primarily on the open mode and how it can enable creativity and innovation. Open Mode thinking is a way of operating for individuals and teams that maximizes the potential for creative breakthroughs.

The Action Mode is

the mode that we are in most of the time when we're at work. We have inside us a feeling that there is lots to be done and we have to get on with it, if we're going to get through it all. [It] is an active, probably slightly anxious mode. (Although anxiety can be exciting and pleasurable.) It's a mode in which we’re probably a little impatient. If only with ourselves. It has a little tension in it. Not much humor. It's a mode in which we're very purposeful, and it's a mode in which we can get stressed, but not creative.

We need to be in the open mode where we're pondering a problem. But once we come up with a solution, we must then switch to the closed mode to implement it. Because once we've made a decision, we are efficient only if we go through with it decisively undistracted by doubts about its correctness. For example, if you decide to leap a ravine, the moment just before, takeoff is a bad time to start reviewing alternative strategies. But here’s the problem. We too often get stuck in the closed mode.

The Open Mode is

relaxed, expansive, [a] less purposeful mode. In which were probably more contemplative, more inclined to humour, which always accompanies a wider perspective and consequently more playful. It's a mood in which curiosity, for its own sake, can operate because we're not under pressure to get a specific thing done quickly. We can play and that is what allows natural creativity to surface.

I think we all know that laughter brings relaxation and that humor makes us playful. Humor is an essential part of spontaneity, an essential part of playfulness and essential part of the creativity that we need to solve problems. No matter how serious they may be.

Feedback

[After a decision has] been carried out, we should once again, switch back to the open mode, to review the feedback arising rising from our action in order to decide whether the course that we have taken is successful or whether we should continue with the next stage of our plan.

Whether we should create an alternative plan to correct any error we perceive and then back into the closed mode again to implement that next stage and so on. In other words, to be at our most efficient, we need to be able to switch backwards and forwards between the two modes. 8

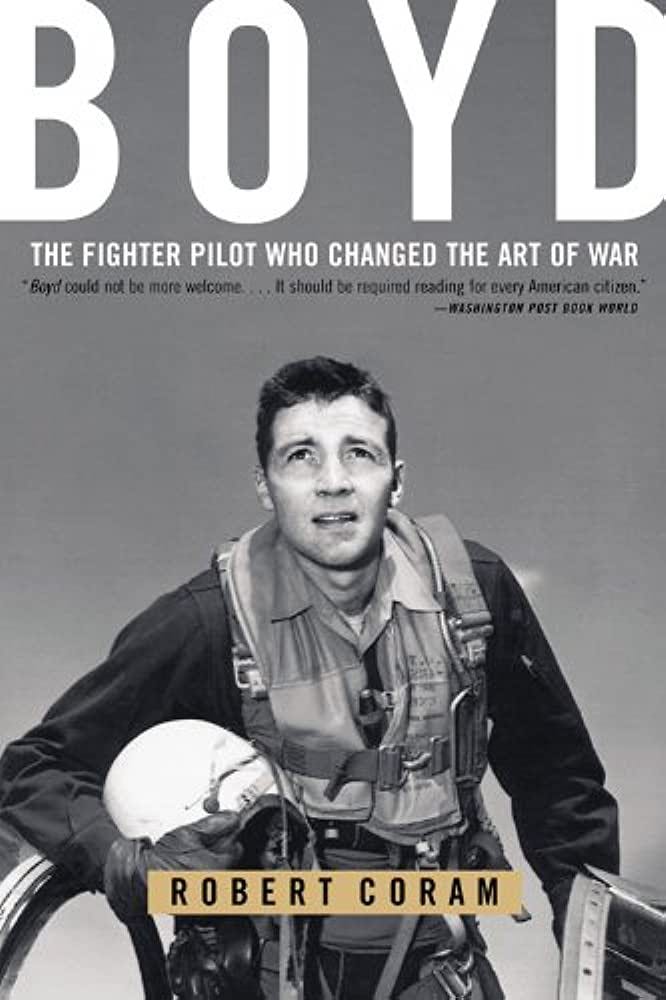

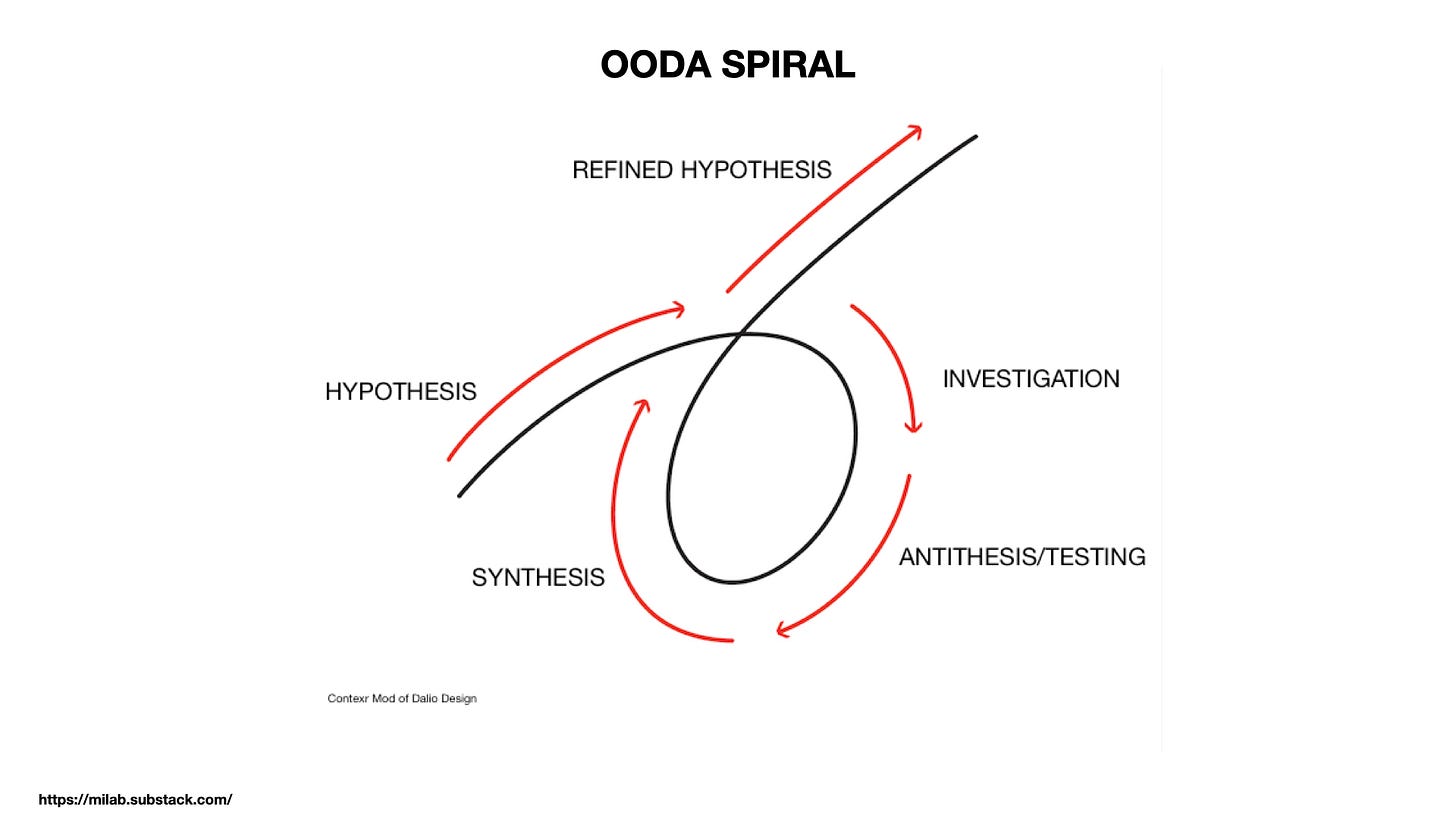

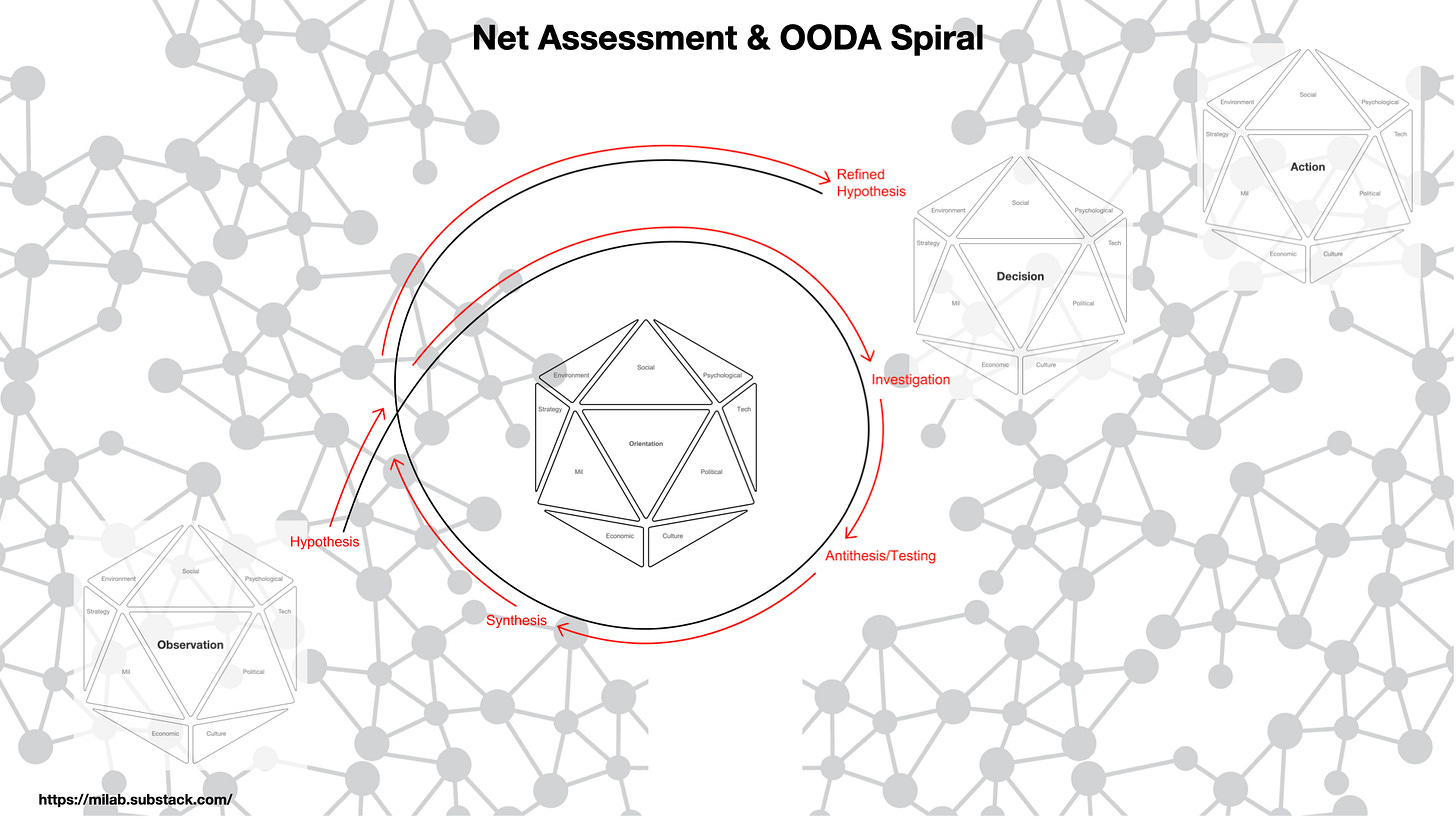

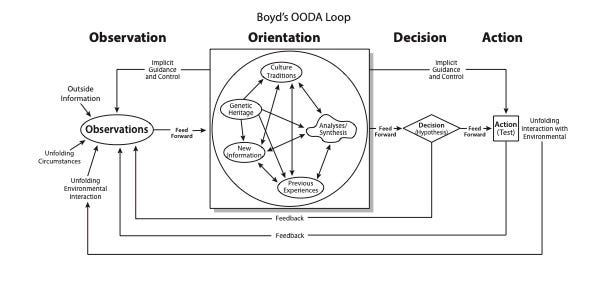

Without knowing it, Cleese has described the OODA loop devised by fighter pilot and military creative, Col John Boyd USAF. OODA stands for “Observation, Orientation, Decision, Action” Loop.9 Boyd created the OODA loop to describe how to win arial combat. The pilot who could ‘get inside the enemy’s OODA loop’ would win. It was all about the speed of decision. In other words, the fighter pilot who was fastest at observing the enemy, orienting her fighter to attack, deciding the right course of action to maneuver to take the shot, and then acting on her decision - would be the victor.

An instructor at the USAFs equivalent of Top Gun, Boyd was known as "Forty Second Boyd" for his standing bet that, beginning from a position of disadvantage, he could defeat any opposing pilot in air combat maneuvering in less than 40 seconds. According to one of his biographers, Robert Coram, he never lost the bet.

OODA also applies to strategic thinking.10 While speed continues to be important, the quality and depth of strategic thinking are additional factors that might give the victor the edge. Here is where Cleese and Boyd really connect. Cleese’s Open Mode thinking is the best method to get quality thought out of strategists.

Traditional military planning processes facilitate action mode thinking. They form the backbone of Command and Staff College curricula. However, there is no equivalent system taught at the war colleges for open mode strategic thinking. General critical thinking skills and studies of strategic texts, Sun Tzu and Clausewitz, make up the education platform. It is useful but students often cant grasp how to apply it to their profession. In future articles, MILab will address this issue in more detail.

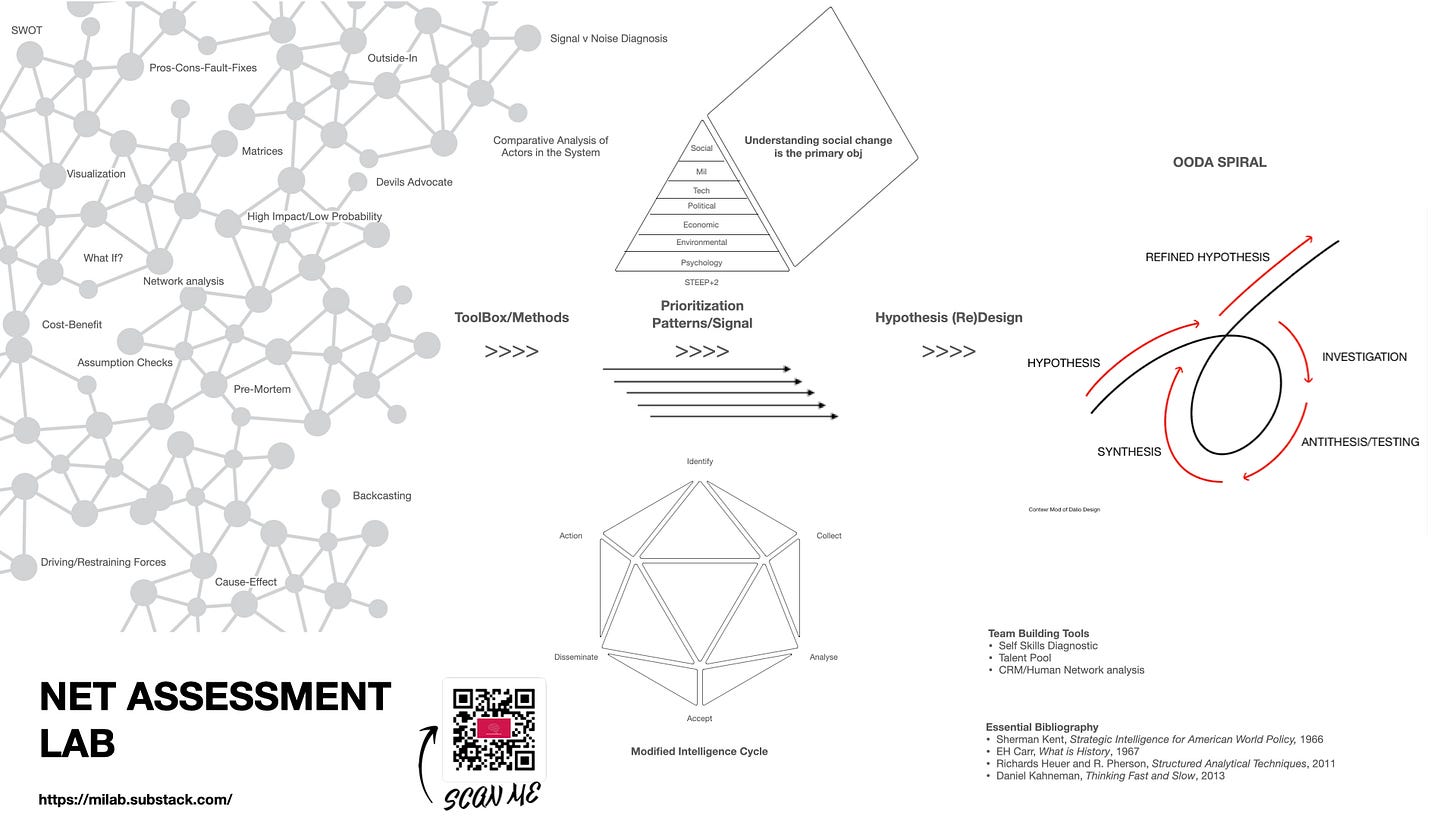

In short, MILab has extended Cleese’s concept, using Boyd, to devise a net assessment design approach to strategic thinking. The MILab system adapts Boyd’s loop into a spiral via the application of dialectical reasoning that accepts there is no end state, just a series of hypotheses that get tested and refuted and refined into a new hypothesis. The spiral represents growth and the accumulation of wisdom. It also acknowledges social phenomena are typically wickedly complex and insoluble. The implication being analysis never ends, it just has systematic waypoints. To accommodate that reality, structured analytical techniques needs to be applied both to the subject matter and the design. A net assessment design extends this article’s discussion of open mode thinking to its application in war. The following is a graphical depiction of the concept that will be the subject of a future article on MILab.

How to be Creative

So we have given aspiring innovators permission to play and have fun. We have sidelined the creativity-stifling self-important pompous jerks who cannot take a joke. The question remains, how does one operationalize humor to get creative thinking on strategy? The first secret is this:

Creativity is not a talent. It is not a talent. It is a way of operating.

It is remarkably simple

You create boundaries of time by arranging, for a specific period, to reserve your boundaries of space.

Sounds like "Forty Second Boyd" but it was, in fact, Cleese.

Cleese and Skinner identified key behaviors that can help to foster creativity and Open Mode thinking. MILab has modified and adapted the list:

Space - allowing yourself the physical and mental space to think and explore ideas without distractions or interruptions.

Time - giving yourself enough time to play with ideas, without rushing to a conclusion or solution too quickly.

Time off - taking breaks and allowing your mind to rest and recharge, which can actually help you to be more creative in the long run.

Discomfort - is a valuable stimulus to resolution - embrace it, don’t reject it.

Speed - open mode thinking maps to two different theories about deliberative versus instinctual decision making.

Confidence - having the confidence to take risks and try new things, even if they seem unconventional or uncertain.

Possibilism - a permission structure and a framework for thinking differently.

Humor - approaching problems with a playful and light-hearted attitude, which can help to spark new ideas and connections. If someone is self important and ridicules humor as an operating system - beware.

Let’s explore these in a little more detail. Points 1-3 are commingled.

Space/Time/Time Off

We create an oasis of quiet for ourselves by setting boundaries of space and of time. Now, creativity can happen.

The key is no interruptions. The push and pull of distraction is at all time extreme levels. The attention industrial complex mounts constant assaults on even the shortest period of uninterrupted time. By design, your smart phone uses casino technology principles to grab your attention with a stream of unending high-pitched “pings” and colorful flashing lights.

Critical thinking is hard and we tend to allow or indeed, crave, distractions instead of knuckling down to really concentrate on something. We all do it. MILab’s inbox and desk have to be whistle clean before he runs out of excuses for setting the right environment for reflection and writing.11

Cleese cautions against procrastination and how to beat it. You have to build an oasis.

It's easier to do trivial things that are urgent than it is to do important things that are not urgent - like thinking. It's also easier to do little things we know we can do than to start on big things that we're not so sure about.

So when I say create an oasis of quiet, know that when you have, your mind will pretty soon start racing again, but you are not going to take that very seriously, you just sit there for a bit tolerating the racing and the slight anxiety that comes with that. And after a time, your mind will quieten down again.

It is essential to silence the phone and the computer from all notifications.12 To ensure your assistant knows no one is to be allowed past their desk, unless the building is on fire. To get back to a full state of concentration can take 15-20 mins so any disruption eats precious time.

Taking time off refers to breaks on projects as well as vacation time. Good writers always say they can’t revisit a piece until some days or even weeks have past. Culturally, the European and American approach to vacations could not be further apart. The European model seems indulgent. But it’s smarter because it facilitates a full break. Subconsciously, the hamster is still running on that wheel, and may even produce some solutions. A full reset is far more likely to generate fresh ideas than scraping a few days off the back of a long weekend and calling that an annual vacation.

Discomfort

The next step is fascinating. Cleese wants you to enjoy discomfort. Critical thinking is hard, takes a lot of time and energy, must be done “right”.13 Failure to find a ready/easy answer causes “a kind of internal agitation, or uncertainty that makes us just plain uncomfortable”.

We want to get rid of that discomfort. So in order to do so, we take a decision. Not because we're sure it's the best decision, but because taking it will make us feel better.

You see, leaving a question unresolved, just leaving it open, makes some people anxious. They worry. And if they cant tolerate that mild discomfort, they go ahead and rush the decision. They probably fool themselves that they’re being decisive. Creative people are much better at tolerating the vague sense of worry that we all get when when we leave something unresolved.14

How did Cleese know this? He discovered the extensive research on creativity conducted by Donald MacKinnon.15 Cleese was aware that certain techniques he used worked. But he could not explain why, until he found that MacKinnon’s research mapped to Cleese’s own personal practices. MacKinnon

discovered that the most creative professionals always played with the problem for much longer before they tried to resolve it. Because they were prepared to tolerate that slight discomfort.

His study of creative architects found they were no more intelligent than others. The key difference was they had a sense of play and they “deferred making decisions for as long as they were allowed”. As Cleese says, there is always a cut-off point but it would be foolish to make a decision before that moment because

You may get new information

You may get new ideas

In war, the concept of discomfort is more ambiguous because generally speaking it is not like the routine of a regular workplace with set projects on pre-agreed deadlines. Warfare is fluid, constantly changing, characterized by fog, friction, and surprise, where there is no such thing as perfect knowledge of ones own forces and significant blank spaces on the other side of the hill.

In the wrong hands, waiting for new information or ideas could become debilitating and dangerous. Indecision is a decision. This is why good leadership is so critical in reading a constantly fluid environment and exercising judgement on when is the right time to act. Some commanders have this knack.16 Others need to work with their staff. A sensibly derived hard decision point may revolve around (friend or foe), (anticipated), changes in political circumstances, seasonal weather patterns, access to favorable terrain and/or lines of communication, availability of logistics (or other support), troop rotation requirements; the list is endless.

A strong commander who engages their staff in open thinking in the plans phase, will be able to take advantage of new information and ideas, when factoring in the pertinent operational constraints and potential opportunities, without squandering “the right moment”. There are no guarantees, and the enemy gets a vote. But this approach is far more likely to bear fruit than arbitrary deadlines and/or endless delay hoping for better circumstances to come along. Unless your opponent is hopelessly stupid, you have to create your own opportunities.17 This is why there is so much focus on the slippery and elusive concept of leadership - what is it, how it can be created, cultivated, and enhanced. The science of war is a tame challenge. The art of war is a wicked opportunity.18

Speed

Indulging in discomfort raises the issue of speed of thinking and decision marking. Clearly discomfort cant be rushed. The most interesting factor here is the correlation between research in psychology and economics regarding the impact of speed. Cleese’s ‘action’ and ‘open’ mode thinking (1991) correlates with what Guy Clayton characterized as “hare brain and tortoise mind” in 2004 and Kahneman called thinking “fast and slow” in 2011.19

Clayton utilizes the Hare and Tortoise fable to describe two different modes of thinking.

"Hare-brained thinking works best when the problem is straight forward, logistical, clearly defined. We know what kind of answer we need, we know what factors are involved, we have all the information we need and we can rely on the measurements we've been given.

Tortoise mind works best in complex, ill-defined situations when we are not quite sure what sort of answer we are after, where it's not clear how many factors are involved, where we may not have all the information, and where its hard or impossible to measure the factors. Tortoise thinking is less purposeful and clear-cut, makes fewer assumptions, is more playful, leisurely and dreamy... being contemplative or meditative. Pondering a problem, rather than earnestly trying to solve it". Tortoise is "curios, open-minded.. it has no problem with vagueness or confusion.. It looks, without deciding in advance what its looking for"

Kahneman explains the cognitive distortions within both kinds of thought processes and how to try and avoid them.20 What unites them all, is a caution against always falling into the default position of fast thinking. Slow thinking, with its rigors and depth, are particularly well suited to wrestle wicked problems.

In 1973 Horst Ritter and Melvin Webber wrote an article that was to become a classic. They explained how some problems, particularly those involving human interaction, are so wickedly complex that they defy solution. Tame problems live in the world of the hard sciences, where issues are quantifiable: they can be measured, compared, contrasted, analyzed and solved. Tame problems are not necessarily simple. They can be incredibly complex - like how to fly a spaceship to Mars and back. Tame problems can be solved by following established rules. Wicked problems can not.

As distinguished from problems in the natural sciences, which are definable and separable and may have solutions that are findable, wicked problems - those dealing with big complex social systems - are not 'solveable' in the way maths or chess have set identifiable solutions. Wicked problems-are ill-defined; there are no true or false answers. There are no criteria which enable one to prove that all solutions to a wicked problem have been identified and considered. There are no classes of wicked problems in the sense that principles of solution can be developed to fit all members of a class. Social problems are never solved. They rely upon elusive political judgment for resolution. At best they are only re-solved--over and over again. Every wicked problem can be considered to be a symptom of another problem.

All strategic problems are wicked, thereby demanding open mode thinking. The time/speed balance is a tough one to strike when there are no “deadlines” in terms of civilian workflows. They are best self imposed. Otherwise, circumstances or the enemy will impose them. In those cases, they are never on terms favorable to the commander.

Strategic thinking must be done in the open mode. It must be given sufficient time. It must also use a rigorous methodology that does not force simplistic “tame” solutions onto wicked problems. To avoid this trap, strategic thinkers have to be comfortable with discomfort and ambiguity and avoid taking short cuts that result in counterproductive or outright dangerous outcomes.

Confidence

Building confidence in a group is not easy and can be fragile at first - especially before group bonds have formed.

If there's one person around who makes you feel defensive, you lose the confidence to play and it's goodbye creativity. So always make sure your play friends are people you like and trust.

Managing misperceptions and disabling distrust requires constant gardening by the leader. A military staff that is ready for open mode thinking has to be “confident, responsible, reflective, innovative, [and] engaged”. To attain these attributes, the team must be encouraged to adopt individual and group skills of “perseverance, self-control, attentiveness, resilience to adversity, openness to experience, empathy and tolerance of diverse opinions

an ability to tolerate uncertainty and persevere at a task to overcome obstacles

not being afraid to make and learn from mistakes

an ability to suspend judgement while generating ideas

willingness to take sensible risks or go out of their comfort zone in their work.

A creative [staff officer] needs to be able to develop and apply a set of skills that they can use in the open thinking mode. These include being able to:

clarify, analyse and re-define the problem or question to uncover new ways of looking at it

ask thoughtful questions

notice connections between seemingly unrelated subject matter

challenge established wisdom by asking: how would I improve this?

recognise alternative possibilities

look at things from different perspectives.”21

To read about the techniques to build a successful military staff see:

MILab has found it useful to characterize strategic planning a laboratory, rather than staff work. Peoples expectations of what happens are instantly different when you change the context within which an activity takes place.

Laboratories are places where exploration happens. They are free from the restrictions and inhibitions of the social world: preconceived ideas, power of personality, deference/obedience to rank, time or resource constraints, and predetermined outcomes. They are places where facts are derived from the observation and testing of evidence. If sufficient numbers of observed facts appear to form patters, then hypotheses are developed to explain the patterns. These in turn get tested against evidence and counter-hypotheses designed to falsify the hypotheses in a search for the truth.

The term Military Innovation Lab was very deliberately chosen to emphasize the concept of experimentation and the pursuit of knowledge free from things that inhibit creativity. In military parlance, a “testing range” for ideas. It is impossible to completely remove the restrictions and inhibitions of the social world from a human endeavor. However, making overt efforts to be aware of the threats to free and open thinking can help military staffs resist the pitfalls and maximize the benefits of experimentation.

To play is [to] experiment. What if the very essence that playfulness is an openness to anything that may happen, the feeling that whatever happens, it's okay. So, you cannot be playful if you're frightened that moving in some direction will be wrong. Something you shouldn't have done. You're either free to play or you're not, as Alan Watts puts it. You can't be spontaneous within reason. Nothing will stop you being creative so effectively, as the fear of making a mistake. So you've got to risk saying things that are silly and illogical and wrong. And the best way to get the confidence to do that is to know that while you're being creative nothing is wrong. There's no such thing as a mistake and any drivel may lead to the breakthrough.

For open mode thinking to work, the participants have to trust the process and one another. People will not speak freely if they fear they might make a mistake or be ridiculed for their ideas. This is why there are certain steps a leader must make at the very start to ensure all participants feel free to make a contribution without fear of negative feedback. The concept of a Lab depersonalizes open mode thinking by putting the emphasis on the idea instead of the speaker and treating everything as contingent.

Once bonds start forming, especially if the leader and/or group are adept as using humor to diffuse tension and move the conversation along, the heavy lifting ends and the group begins to police itself. To get there, Cleese suggests reframing away from the speaker to the question itself.

Don’t ask who is right. Ask which idea is better.22

A subtle and very important distinction that takes personalities out of it. This technique helps elevate discourse toward productive disagreement. This is a skill that does not happen naturally. It needs to be cultivated. The pyramid below can be a learning tool to explain to the group how to disagree and to encourage movement to the peak of Bloom’s taxonomy (above) - creativity. Even if everyone is a university graduate, there is no guarantee they will have been exposed to the rules of logic and discourse. Using this rubric reinforces the importance of focusing on the ideas and makes discussion a lot smoother.

Cleese’s usefully offers some useful techniques for leaders to build group confidence. The essence of which is “never say, ‘no’ or ‘[thats]'wrong’, or ‘I don't like that’… Never say anything to squash [contributions or their authors].”

Try to establish as free an atmosphere as possible. Always be positive and build on what's being said. [Ask questions like] “Would it be even better?”, “I don't quite understand that”, “can you just explain it again?”, “go on?”, “What if”, “Lets pretend”“I wonder why”, “what are the reasons”, “I am puzzled by...”, “how would it be different if...:, “what if we knew...?”, “if I could interview the [general or enemy], I’d ask...”, “what happens if I do this?”, “what would happen if we did that?”

Andragogy is distinct from pedagogy in that it is not about finding technically correct answers. It is about exploring possibilities. Chat GPT and Google can give you answers.23 They cannot explore possibilities.

Possibilism

Possibilism is essential to MILab thinking. Pessimism and optimism are emotional states. Emotion has no purpose in strategic thinking. It is the essence of friction. Possibilism sees the world as it is, not as we wish it to be. It is concerned with unrestricted curiosity-driven, reason-based, problem-solving. Possibilism looks for ways to find advantage in chaos. It demands challenges are examined for opportunities. Possibilists have "a worldview that is constructive and useful. [They] neither hope without reason, nor fear without reason.”24 Possibilist organizations are designed to deliver optionality to decision making via a thorough analysis of the context around an opportunity. It is interested in disproving ‘no’ as an answer. Possibilist’s use a methodology that critically reexamines everything we think we know to find new contexts (situations, associations or relationships) that can help create constructive solutions. In the world of grand strategy and military operations, things are constantly changing in ways that are not always obvious ‘to the naked eye’.

Humor

The removal of friction in any learning setting is contingent on listening, mutual respect and empathy. These are all evidence of a confident group. Once barriers to listening are cleared and the group develops confidence in itself, then the power of the group to deliver collaborative insights and creative outcomes will be hard to shake. That is also when the fun really begins. MILab has experienced this personally many times.25

Humor is the most effective vehicle to rapidly get there.26

Humor is an essential part of spontaneity, an essential part of playfulness and essential part of the creativity that we need to solve problems.

I think we all know that laughter brings relaxation and that humor makes us playful. I happen to think the main evolutionary significance of humor is that it gets us from the action mode to the open mode quicker than anything else.

The fastest way to bring people together is humor. It is a great pressure release valve if a topic is unpleasant, complicated, boring or debate gets too heated. Humor is a great leveler - it puts all players onto a level playing field. A witty quip can break the ice, tension or boredom. The most effective way to read a room is to provoke a smile. Humor can remove the threat of ‘novelty’ and/or ‘difference’. It is also a way to forge new connections between disparate data or hypotheses.

In a joke the laugh comes at a moment when you connect two different frameworks of reference in a new way. Having an idea, a new idea is exactly the same thing. It's connecting to hitherto separate ideas in a way that generates new meaning.

Just don’t get too counter cultural

This is why military creatives are perceived by the mainstream culture as, at best disruptive, and at worst, traitors. Being a “disruptor” is trendy now. Maybe thats an advance? MILab is not so sure… It is worth considering that innovators like John Paul Jones, Billy Mitchell, Giulio Douhet, Pete Ellis, Alan Turing, Robert Oppenheimer, John Boyd, and many others were all considered "difficult" people. All were either criticized on personal grounds, ignored, sanctioned, outcast, or destroyed by the culture they served. It reminds MILab of the bumper sticker:

Emotional criticisms of a person’s disposition is the easiest way to discredit them. It is the weakest way too. It is the classic case of playing the woman, not the ball. Let’s face it, none of his critics could take Oppenheimer on physics or discussions on the future implications of the bomb. So calling him a communist worked just fine. “Problem” solved.

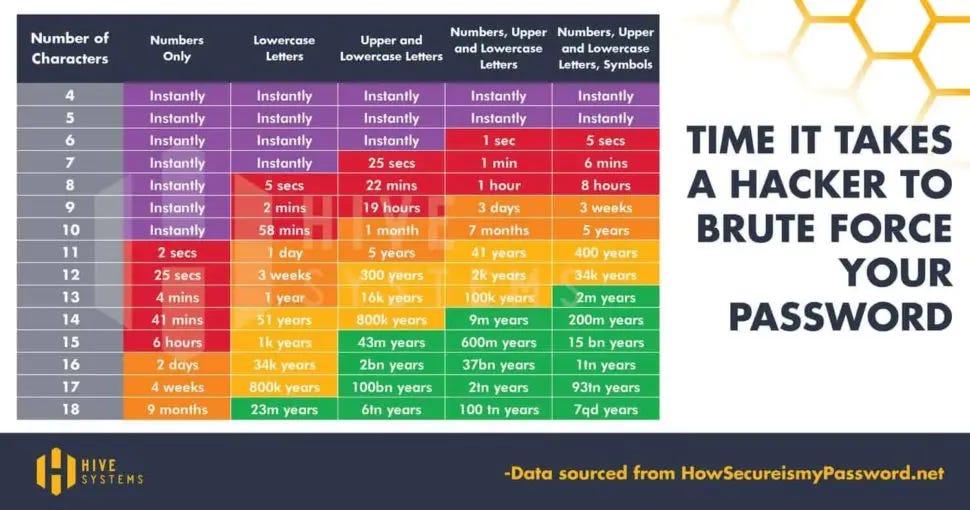

In WWII the Germans used a coding machine called the Enigma. At its peak, it had 158,962,555,217,826,360,000 different settings (159 quintillion where a quintillion is 1030).27 Using modern computers, it took 1,726 days to crack a code of that complexity. Initially using just pencil and paper, Alan Turing devised a method, and later a machine, that could crack the code in 20 mins.28 Turing was an extraordinary genius. A Mozart of mathematics.29 His ideas were crucial to breaking the German enigma codes, so that the allies knew enemy intent and plans in advance. Intent is the Holy Grail of intelligence. The official historian of British intelligence in WWII (MILabs PhD supervisor - who worked with Turing at Bletchley) conservatively estimated Turing's genius shortened the war by 2 years - sparing millions of lives. He should have been given all the honors owed a great war hero in the manner the Brits do best - like Marlborough or Wellington. Instead, Turing was gay when that was illegal in the UK. He was castrated and committed suicide.

Maligning thinkers as traitors or worse, is a simple and effective way to silence them. Most people don’t take the time to read the back story and critically evaluate the facts. Some get redemption and even national apologies long after they die. John Paul Jones was dug up from his paupers grave in Paris, shipped home, and put in a replica of Napoloen’s tomb.30 Turning was pardoned by HM the Queen and is on the £50 note. Oppenheimer was finally rehabilitated last December in advance of a major motion picture on his life that will be released in July.

The Threat of Creativity

Cleese ends his brilliant talk by reversing his recommendations to show how the world usually works.

How to stop your subordinates becoming creative - which is the real threat. Because believe me, no one appreciates better than I do, what trouble creative people are and how they stopped decisive hard-nosed bastards like us from running organizations efficiently. I mean, we all know. We encourage someone to be creative. The next thing is, they're rocking the boat coming up with ideas and asking us questions. Now, if we don't nip this kind of thing in the bud, we will have to stop justifying our decision by reasoned argument and sharing information, the concealment of which gives us considerable advantages in our power struggle.

So here is how to Stamp Out creativity in the rest of the organization and get a bit of respect going. One, allow subordinates no humor. It threatens your self importance, especially your omniscience. Treat all humor as frivolous or subversive. Because subversive is of course, what humor will be in your organisation as it's the only way that people can express their opposition. Since if they express it openly you're down on them like a ton of bricks. So let's get this clear. Blame humor for the resistance that your way of working creates, then you don't have to blame your way of working. This is important. And I mean that solemnly, your dignity is no laughing matter .

Second, keeping ourselves feeling irreplaceable, involves cutting everybody else down to size. So don't miss an opportunity to undermine your employees confidence. A perfect opportunity comes when you're reviewing work that they've done. Use your authority to zero in immediately on all the things you can find wrong. Never, never, balance the negatives with positive. Only criticize, just as your school teachers did. Always remember, praise makes people uppity.

Third demand, that people should always be actively doing things. If you catch anybody pondering, accuse them of laziness and or indecision. This is to starve employees of thinking time because that leads to creativity and Insurrection. So demand urgency at all time, use lots of fighting talk and war analogies and establish a permanent atmosphere of stress, of breathless, anxiety, and crisis.

Keep that mode closed. In this way, we no-nonsense types can be sure that the tiny microscopic quantity of creativity in our organization will all be ours. But let your vigilance slip for one moment, and you could find yourself surrounded by happy enthusiastic and creative people who you might never be able to completely control ever again, so be careful. Thank you, and goodnight.

Cleese on Creativity - the full speech (36min)

In the next article MILab will take the open mode system further. We will discuss what design thinking offers strategists and how a net assessment approach can be used to circumvent the pitfalls of bad strategy making.

John Cleese, Creativity in Management: A Speech to an International Audience, Grosvenor House, London, 23rd Jan 1991

The following quotes are all from the Cambridge Assessment International Education, Developing the Cambridge Learner Attributes, Cambridge University Press, 2011

Carol Cohn, “Sex and Death in the Rational World of Defense Intellectuals”, Signs , Summer, 1987, Vol. 12, No. 4, Within and Without: Women, Gender, and Theory (Summer, 1987), pp. 687-718, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3174209. This is one of MILabs all time favorite articles because it is rich with cross cultural misunderstandings but also some genuinely funny insights into strategic culture. “Pat the weapon” will go down in history as hilarious but also insightful about the coping mechanisms people create to work on otherwise horrific issues. Nuclear weapons and warfare are here to stay. So no matter how unpleasant, it must be analyzed and efforts made by professionals to ensure it never happens. If they make that task easier by using humor to deflect from the stress of managing armageddon, and not as a means of trivializing what’s at stake, then it has a purpose.

John Cleese, Creativity in Management: A Speech to an International Audience, Grosvenor House, London, 23rd JAN 1991. The bulk of the texted used in this article is from this remarkable speech. Other works include John Cleese, Creativity: A Short and Cheerful Guide, Penguin, London 2022. Robin Skinner, John Cleese, Life and How to Survive It: An Entertaining and Mind-Stretching Search for What Really Matters in Life, 1994, NY, WW Norton.

Thinking about how we think is called epistemology. It is defined as “the theory of knowledge, especially with regard to its methods, validity, and scope. Epistemology is the investigation of what distinguishes justified belief from opinion.”

This choice of words Is deliberate. Accurately knowing “why” is the hardest part of war.

Clausewitz "The most far-reaching act of judgment that the statesman and commander have to make is to establish…the kind of war on which they are embarking; neither mistaking it for, nor trying to turn it into, something that is alien to its nature." .

Sun Tzu “Know the enemy and know yourself in a hundred battles you will never be in peril”.

The classic example is the Japanese decision making before Pearl Harbour. They debated the “who”, “when”, and “how” in great depth. They never debated the “why”. It was obvious to all, or so they assumed. Recall that Pearl Harbor was only one part of a theatre-wide operation that included the first and second island chains. Had they fully explored the assumptions behind, and reasoning for, the US part of the operation, they might have had an opportunity to foresee its pitfalls and/or cancelled or improved it (third wave/fuel tanks/carriers/occupying the island etc). Yamamoto was later to have written “I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve.” As with everything, this is now disputed. But the point stands.

MILab was on a staff that received a delegation from the PLA-AF. After the senior general insulted his American hosts by saying America deserved 9/11, MILab asked him why he did not have wings like the other generals and colonels in his delegation. The others sniggered under their breath as the senior general admitted sheepishly that he was the “commissar general”. Later MILab asked him about what they would do in a certain low level operational hypothetical for which an American officer would have a ready answer. The commissar general genuinely had no idea and admitted “I would have to ask Beijing what to do”. When pressed on this being a weak answer he further admitted that even he did not have authority in relatively low level scenarios. This was the most telling insight MILab had in years of observations of the Chinese.

A friend in military intelligence and I were talking about these topics recently and we started to discuss why intel shops tend to ask and answer their own questions when they should be supporting operations. The critical missing link is feedback, according to my friend who has 20 years in intel, first as an enlisted combat tour veteran, then as a senior analyst with a PhD. We both have noticed that there is often a disconnect between the incredibly exquisite IC assets, capabilities, and analysis; and those who need the data and knowledge to do their jobs. We were discussing the kind of organization that needed to be created to bridge the gap. He put it perfectly - what is missing is the clutch. In short, think of a stick shift car. We have a huge and incredibly powerful engine (NSC, IC, DOD) but the power is not getting to the wheels (policy and operations delivering desired outcomes in grand strategy). A net assessment center, like the one MILab will propose in a future article, can act like a clutch, transferring that power to the wheels and giving feedback to the driver so she knows if she is getting too little or too much traction and needs to apply more power or the break to avoid an accident.

He also just described the Hegelian dialectic where a contradiction between a proposition (thesis) and its antithesis is resolved at a higher level of truth (synthesis). When this concentrates on disproving a proposition it conforms to Poppers refutation imperative where ‘real scientists’ try to refute, not confirm, their theories.

This book is a labor of love of one of his biographers, Grant Hammond at Air University. Grant took the 350+ Boyd “slide presentation” - that took a total of 15 hours to deliver - and turned it into this book. Slide presentation is in quotes because this was generated pre powerpoint. These are from the old plastic sheets that were put on a burning hot light that shined on a wall. Yep. Old school. It’s a miracle a complete set were available. So beware, the “book” is really a slide set. If you can get a hard copy (a dear friend set me one), it is a lot easier than digital. I recommend this book not only because it’s easily downloaded but it also has QR coded links to YouTube videos of Boyd himself giving his lecture. The quality is not great but it is the best we have. Boyd never wrote a book.

The process of writing analytical assessments, in and of itself, is vitally important for forcing logic, driven by solid evidence, against a difficult problem. The process of writing always reveals connections, challenges and opportunities that otherwise would lay dormant.

It is possible to set things up so that only one phone number can get through in case of a real emergency. But let’s not kid ourselves here. If you can’t set aside 8-11 am two days a week you have bigger problems in your life and you should not be professionally involved in strategic thinking - because these are minimal professional requirements.

Which is why MILabs spends so much time and effort on methodology.

This section is from Creativity, p.45.

Donald MacKinnon was an eminent psychologist, whose research concentrated on creativity. To say Cleese is a fan is an understatement. MacKinnon initially worked for the OSS, the forerunner of the CIA and US Special Operations Command, as head of Station S in Fairfax Va. This is significant because the wartime psychology work of the OSS was particularly impressive. In 1943, a group of psychology scholars (some in OSS, some contracted from the Ivy’s) produced a remarkable profile of Adolf Hitler that accurately predicted his future behavior in the war. The study is well worth reading today for what it tells us about leadership of authoritarian regimes. See Walter C Longer, et al, A Psychological Analysis of Adolph Hitler: His Life and Legend, Office of Strategic Services, Washington DC. In the 1960s, the wartime use of psychology to understand political leaders was revived when CIA’s “Center for the Analysis of Personality and Political Behavior” was created by Dr Jerrold Post, who built on the incredible legacy of the OSS. Post is rightly considered one of the great innovators in intelligence.

MacKinnon’s wartime OSS work, Assessment of Men: Selection of Personnel for the Office of Strategic Services, 1948, NY Rinehart and Company, “remains a classic in the field of personality testing.” MacKinnon, et al, mapped the characteristics of what would make a good intelligence operative. In a way, it was an antidote to the Hitler study. After leaving the OSS, MacKinnion founded the “Institute of Personality Assessment and Research” at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1949 and served as its director until his 1970 retirement.

“He took to the institute the skills and research techniques he had learned during World War II.” MacKinnon wrote “In Search of Human Effectiveness” in 1978, describing the search for and identification of creative people. In 1981 he was given the Murray Award, one of the top honors in psychology, for his contributions to personality research.

This is true in bureaucracy as it is in war. MILab had one senior boss in particular who had uncannily fine judgement in knowing when to push an initiative and when to wait. This would send the staff up the wall because they knew he was on board for the change but appeared not to push for it when he had the opportunity to do so. This engendered distrust. He could have avoided this by sharing his reasoning with his inner circle. Failure to share his thinking was read by them as distrust. This created a distrust spiral. After a time, MILab could work out what his logic was by observation and the occasional side comment. He was a superior bureaucratic operator - the best MILab has ever seen. But the question always lingered, if he was able to develop real trust with his inner circle, would that have made the operation stronger?

Stupid opponents tend to die early in conflict leaving behind better thinkers whose skills only grow with experience.

“Tame” refers to something that is easily measured, calculated, and answered within known methodological rules. “Wicked” refers to hard to measure, ephemeral, uncertain, unbounded issues that defy easy calculation. You can measure the number of tanks in an army (tame). How do you measure the will of the army and people to fight? (wicked). Horst Ritter, Melvin Webber, Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning, Policy Sciences, 4 (1973) pp.155-169. The context of wicked problems is a theme that MILab returns to frequently because its vital to understanding the difference between the science and art of war and how to usefully approach the latter.

Horst Ritter, Melvin Webber, Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning, Policy Sciences, 4 (1973) pp.155-169. Guy Claxton, Hare Brain, Tortoise Mind, NY, 2004. Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow, NY, 2011.

Kahneman:

Psychologists have been intensely interested for several decades in the two modes of thinking evoked by the picture of the angry woman and by the multiplication problem, and have offered many labels for them. I adopt terms originally proposed by the psychologists Keith Stanovich and Richard West, and will refer to two systems in the mind, System 1 and System 2.

- System 1 operates automatically and quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control.

- System 2 allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it, including complex computations. The operations of System 2 are often associated with the subjective experience of agency, choice, and concentration

Cambridge Assessment International Education, Developing the Cambridge Learner Attributes, Cambridge University Press, 2011

Creativity, p.102

The subject of AI is hot right now. MILab tested ChatGPT. Here is a quick take: It was like next level Google but it had very significant failures. It could handle 2-3 sub-elements of a somewhat complicated initial question and deliver a fairly accurate response. It was good at explaining basic philosophical and military concepts. But it failed at second order interrogatories. In the course of an hour it apologized on three occasions when MILab caught it out for giving inaccurate answers. In one example, it politically manipulated the answer to be the opposite of the truth and then admitted it when confronted with the evidence. This concerned the role of an intelligence official in the run up to January 6. ChatGPT alleged he leaked classified documents and was fired. This was absolutely not the case at all. He was virtually the only official who issued warnings about the emerging threat in advance of the event and resigned when they were not acted upon.

Hans Rosling coined the term possibilism. His thinking is similar to the great International Relations theorist EH Carr, who in The Twenty Years Crisis, was critical of both realism and idealism. Carr argued for an essential interplay between realism and idealism, where the former ensures analysis starts with the world as it is, and the latter provides a basis for imagining alternative worlds and provides a creative platform for reform. As reform hypotheses are developed they are then subject to evaluation and refutation by interrogation grounded in realistic knowledge of the world. Thus a never ending cycle of ‘what might be’ is refined by the limits of ‘what is’ and vice versa.

MILab had a new group at a war college made up of mostly senior 06s fighter jocks, heavy bomber pilots, and ICBM commanders. To this group came a diminutive, minority female naval officer, from a non-combat MOS, who had somehow missed Command and Staff College, and been frocked to 05 to get in. It was like Private Benjamin meets a roomful of Colonel Jessup’s. As a new foreign civilian professor I was out of my cultural depth on this one. I didn’t want to single her out to answer questions - for fear of making her look bad in front of the others with the impact on her personal confidence that would entail. But there was also the minority v majority factors and I had not been in the US long enough to know how to handle that. Thankfully she approached me in my office one day. I had encouraged people to drop by if they had any questions or concerns. She confided in me that she didn’t know anything about strategy and Clausewitz and she was terrified of the group - not because they had been in anyway unwelcoming but just because these guys had done command and staff and they all had the gravitas that comes from successful senior command.

So we hatched a cunning plan! I told her to bring her “most basic” questions to class and I would put them to the group so she could see they didn’t know it all. Once you peel back the first superficial answer and keep pressing for the underlying answers, the “stupid question” can quickly become the “beast question”. Her questions “why cant the center of gravity be the weakest point? Why attack the enemy’s strength?” had the group squirming.

We even agreed a signal for her to give me so I would know I could ask her a question for which she had prepared. She nailed the first question. I could see the Jessup’s eyes dart over to her, then to one another. They knew she nailed it too. Slowly over the next week or so this pattern would repeat. At that point I knew I could ask her anything any time and she would be just fine.

I also insisted everyone use first names. In that context, that was a bit unusual. I came from a country where people get uncomfortable being called Sir. Soon enough we were all on a first name basis. Then as our confidence as a group grew, we started nicknames. I dubbed this officer “Swabby”. Within a month of our little plot, the jocks were all wrapped tight around Swabby’s little finger. She had the smarts and personal flair to carry it off. So armed with a little confidence boost, she flourished, and everyone benefitted. The group was one of the happiest and most fun I ever had the privilege to teach. Everyone set egos aside and genuinely listen to and interacted with everyone else. It was a very creative group of serious senior military professionals and we laughed our asses off all year long.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper Row. (2002, p.99) emphasises the importance of having a playful attitude while remaining disciplined.

This is absurdly simplified. The Enigma was the equivalent of 64 bit encryption. This was broken by computers in brute force attacks in 1726 days. At first, Turing and the team at Bletchley had no computers, just pencil and paper. Later, Turing built a machine to do the calculations once they cracked the initial code set by the rings on the Enigma. The trick was what is now called “social engineering”. Its a big complicated story and Turing was supported by an incredible team, but his intellectual leadership is unquestioned.

My favorite story about young Wolfgang was he heard the Allegri Miserere just once in the Sistine Chapel. The Pope did not let anyone hear the music outside of the Vatican so there were no published scores. Mozart transcribed the entire thing after leaving the building. The complexity of this magnificent and sacred piece of music is astonishing.

The father of the US Navy, the only one to take the fight to the British homeland (the rest of the Navy protected the US eastern approached) died alone, abandoned, and poor as an accused child molester. After the revolutionary war, John Paul Jones, always eager for a scrappy fight, joined the Russian navy. He excelled so much that Potemkin (of empty village fame) was fearful that Catherine the Great might favor JPJ over himself. Next thing you know, JPJ is accused of raping his maids daughter. According to Evan Thomas’ biography on JPJ, he left Russia and returned to Paris where he was shunned for the rest of his life and died alone and broke. It wasn't until over a century later when the USN needed a hero, that he was dug up in Paris and shipped to Annapolis to his Napoleonic-style sarcophagus at the Naval Academy.

Source: Evan Thomas, John Paul Jones: Sailor, Hero, Father of the American Navy, https://tinyurl.com/y37wgvuh